The Essence of the Difference Between Analog and Digital Information

- Continuous and Discrete: Unease with Textbook Definitions

- Digital information is identification information defined by humans

- The key point is whether concepts are associated with the information

- Digital information divorced from concepts has no meaning

- Being discrete does not mean it is digital information

Continuous and Discrete: Unease with Textbook Definitions

What is the fundamental difference between analog and digital information?

Many people would likely answer, “Analog information is continuously changing information, while digital information is discrete information.” Of course, that is probably the textbook answer.

But is that truly the essential difference between analog and digital information?

If we extract only the information at a single instant, the issue of change becomes irrelevant, so the distinction between continuous and discrete loses meaning. The step-second hand of a quartz analog watch rotates in a discrete trajectory.

Well, you could dismiss that as nitpicking, but when teaching students the difference between analog and digital information at work, I just couldn’t bring myself to explain it as “continuous vs. discrete.”

However, over the past few years, while working on documenting the curriculum I’ve developed, it became clear to me that the fundamental difference between analog and digital information lies elsewhere.

The clue was contained within the main theme of my lessons. It is the following idea:

The principle of the computer as a device is independent of its physical implementation and exists within the human mental activity of thought.

As we delve deeper into this theme, it becomes clear that what distinguishes analog information from digital information is whether the information is the information itself or symbolic information representing a corresponding concept.

This fact remains obscure because we fail to observe the spiritual activity of humans—the creators of digital information and the subjects of cognition.

Digital information is identification information defined by humans

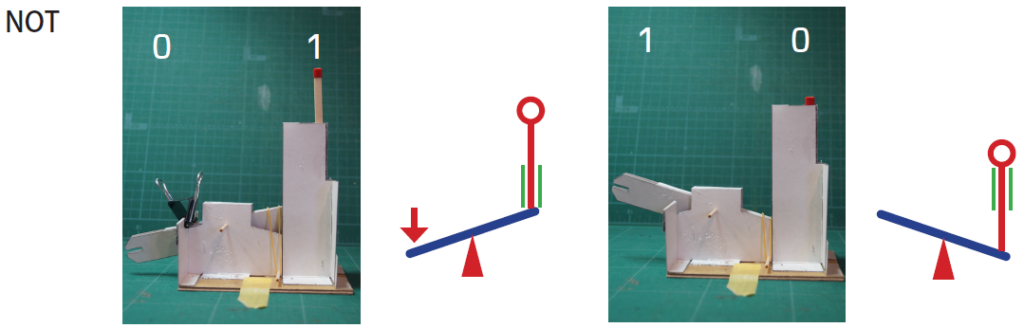

The logic devices that make up digital computers can be realized using gears and cams, or implemented with electronic switches. At the start of every computer class, I always build logic devices with my students using the mechanism of a seesaw.

For example, the seesaw’s property where one side lowers as the other rises can be regarded as the function of NOT logic. However, this is merely a “regarding”—it is simply humans projecting NOT logic onto the seesaw’s motion using their own thinking. The seesaw’s operation itself is nothing more than a board attached to a pivot rotating a fixed angle due to force applied to one end of the board.

We can define the raised position of a seesaw lever as 1, or we can define it as 0. As long as consistency is guaranteed in the definition, the logical device combining these will function correctly. Whether the definition is 0 or 1, the device’s operation does not change.

It is human thought that assigns meaning to the lever’s state.

Let’s confirm this clearly here. The logical state 0 and the logical state 1 are concepts. Concepts belong to humans.

Defining the lever’s up or down state means identifying the lever’s position as an identifier and associating the concepts 0 or 1 with that identifier. Prior to this, only the lever’s up-and-down motion exists. Only after we can associate the identifier with the concept can we derive the concepts 0 or 1 from the lever’s up or down state.

This is digital information. And it resembles something.

By learning letters, we associate the concept of the phoneme éɪ with the symbol A. This act is no different from defining 0 or 1 for the lever’s up/down position. Therefore, letters on paper are also digital information.

When we recognize the symbol A, we represent the concept of the phoneme éɪ. Similarly, when we recognize the state of the seesaw lever being up, we represent the concept of 0 or 1 that we defined beforehand.

The key point is whether concepts are associated with the information

By now, I believe the following has become clear.

- Analog information: The quantitative information itself constitutes the intended information. Information that exists in this manner is analog information.

- Digital information: The information itself is an identifier = ID, and has no meaning in and of itself. The concept linked to that identifier is the intended information. Thus, information where information and concept form a pair is digital information.

Analog information

Light and shadow, color, intensity, angle, mass, volume, distance, etc.

Quantitative information → the information itself

*Quantitative changes directly result in information degradation.

Digital information

Characters, numbers, symbols, patterns, etc. (functioning as ID information linked to specific concepts)

ID information

→ Concepts uniquely linked to an ID through human thought

*If the ID information can be identified, the corresponding unique concept can be obtained without degradation.

How about that? This has cleared up the lingering doubts nicely.

Digital information divorced from concepts has no meaning

The beads of an abacus, characters on paper, magnetic information patterns, bit patterns in memory—all are digital information. On the abacus, the position of the beads is linked to the concept of number. Characters on paper point to the concept of phonemes or meaning associated with their form. The same holds true for magnetic patterns and bit patterns.

We know that one bead (ichidama) raised on each digit of the abacus represents 1. Two beads represent 2. And if the five-bead (godama) is raised, it signifies 5. We understand that together with the value indicated by the one bead, this represents one digit in the decimal system.

This is because we already possess the concept of the abacus’s definition, which has been shaped over the course of history, allowing us to understand it. Human thought links the fixed patterns created by the state of each bead with numerical concepts. The way these fixed patterns and numerical concepts are uniquely linked mirrors the way integer values are used as identifiers.

Thus, digital information itself is like an identifier or ID, holding no meaning in and of itself. For that information to have meaning, the identifier must be linked to a concept. It is human thought that makes this connection. Digital information without human involvement has no meaning whatsoever.

This fact holds profound significance for understanding computer technology.

Even digital information meaningful to humans is merely a meaningless pattern to computers. The concepts linked to that pattern exist only within humans.

In this sense, the notion that computers operate in binary is also an illusion.

Only humans view binary bit patterns as numerical concepts; to computers, they are merely patterns. Computers associate the numerical concepts of 0 and 1 with specific states in memory, treating their sequence as binary numbers for operation. This is no different from moving beads on an abacus to perform calculations. Computers process it strictly as a pattern.

Humans prepare programs as consistent procedures that ensure these patterns are manipulated according to binary arithmetic rules, then instruct computers to execute them. Computers manipulate the “patterns” exactly as the program directs. There is no inherent meaning within this manipulation itself. The meaning of the operation exists outside the computer, as the thought content: “Manipulating this pattern in this way produces a pattern consistent with binary arithmetic.”

Some might think, “If you can recognize the logic by reading the program, then that logic must exist inside the computer.” This is only because they overlook the fact that the act of “reading the program” is itself a mental activity of the reader.

The program itself contains no logic; it consists solely of a collection of discrete procedural units. Only humans, as thinking beings, can integrate these discrete procedural units, grasp them as a coherent program, and connect them to the concept of purpose.

In this way, a certain pattern remains in memory as the result of executing a program (a set of discrete procedures). Humans read this pattern in some manner, recall the numerical concept associated with it, and give meaning to that information by representing it within themselves.

No matter how advanced an AI may be, it cannot be an exception to this.

Being discrete does not mean it is digital information

Considering this, it becomes clear that the notion of digital information being discrete because it is discrete is putting the cart before the horse.

Digital information is discrete because its essence is that of an identifier. It is not the other way around.

For example, the codes 4116 and 4216, representing A and B in ASCII, have no inherent relationship between them. They could be entirely different numerical values, and fundamentally, they aren’t even numbers—they are symbol patterns for identifying phonetic concepts.

Assigning ordinal numbers to character codes to represent the ABC sequence serves to express a higher-level conceptual system rather than merely an alphabet set, which itself becomes another element for consideration.

コメント