Internet

Created by Masashi Satoh | 11/23/2025

The source of the title image: Lokilech at German Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

Introduction

Through building a relay-based adding machine, we learned the fundamental mechanisms of computers and the basics of information transmission together with our students.

Before this learning solidifies, we will immediately proceed to cover the fundamentals of Internet technology. This is because it presents a perfect opportunity for students to vividly imagine how the computers they just learned about are tirelessly transmitting information day and night within the immense number of nodes connecting the Internet network.

Many Waldorf school children have likely learned without exposure to computers and other electronic media, at least until upper elementary school. This practice is likely followed to a significant extent in their homes as well.

To reach the depths of such pure hearts, Waldorf education maximizes the use of its human-centered approach. Of course, this approach also works for children who have already been exposed to media. And for adults too.

It is important to advance learning within the human-centered context of Waldorf education. Here, we introduce an excellent teaching material suited to this approach: the optical telegraphy system developed by the Frenchman Claude Chappe.

Some may wonder why we study such historical relics when learning cutting-edge technology. However, once you understand the network system Claude Chappe implemented, you’ll realize it was essentially the precursor to today’s internet—a system operated by people instead of machines. And the fact that this was a mechanism powered by human labor is the key to understanding it.

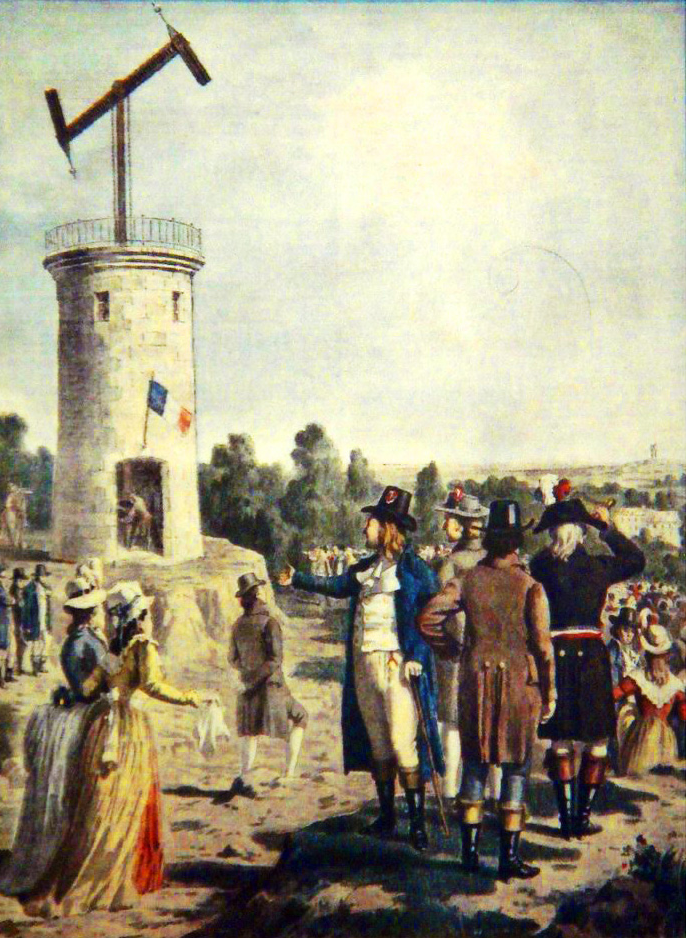

The Dawn of the Internet as Seen by Napoleon

Internet technology during the French Revolution

Now, let us begin our story.

First, take a look at this. What is it? An antenna? No, it’s not.

This tower has windows on both sides, and inside there is a person who alternately looks through telescopes pointed toward each window.

In the same room is a pulley system with two handles; moving these handles causes the arm on the roof to pose accordingly.

In fact, these towers are dotted every few kilometers, each equipped with the same apparatus and staffed by personnel in the same manner.

The person inside constantly watches the shape of the arm on the neighboring tower. As soon as the neighboring arm begins to move, they immediately operate their tower’s arm to match that shape. Then, they wait for the arm on the opposite tower to respond in kind, before turning their attention back to the movement of the first arm.

By repeating this procedure, it was a device that transmitted information like a bucket relay.

If you’re not paying attention, you might not notice, but this device uses optical communication technology. In fact, surprisingly, communication using this device was capable of delivering information to distant locations at speeds 3 to 5 times faster than the speed of sound!

Even more astonishingly, communications via this device were encrypted, featured error correction capabilities, could reliably deliver messages to specified addresses, and enabled two-way communication with collision avoidance protocols. This technology, seemingly anticipating the internet, suddenly appeared in revolutionary France.

Claude Chappe

Henri Rousseau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It began with the French Revolution of 1789.

Claude Chappe was born on December 25, 1763, in a village near Le Mans, France. His uncle, Jean Chappe, was a member of the French Academy of Sciences and had made a name for himself as an expert in astronomy and cartography.

Just as his uncle had pursued science after becoming a clergyman, Chappe also studied theology early in life and was assigned to two small monasteries.

In pre-revolutionary France, the clergy status guaranteed a secure livelihood for life. But then the Revolution struck. It transformed clergy into subjects of the state, stripping them of all their traditional privileges.

In his mid-twenties, Chappe made a major shift in his life plan. He decided to use his knowledge of electricity, which he had long been interested in and had continued to study, to develop a new communication technology. However, electrical science was still immature at the time, and Chappe soon abandoned this approach. After experimenting with various methods that might replace electricity, Chappe arrived at a communication system using a method similar to semaphore flags.

Once this concept took shape, he lobbied the Assembly through his brother, who had become a deputy in the revolutionary government, requesting an official experiment with this communication device.

The success of the experiment

The proposal was shelved for a time, but it was discovered by a discerning figure of influence, and the experiment was realized in July 1793. By this time, Chappe had found a supporter to design the mechanism for the device and was steadily advancing its development. That supporter was the renowned watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Breguet was the darling of his era, having achieved one innovative watchmaking feat after another: the self-winding Perpétuel mechanism for pocket watches, the shock-resistant Parachute escapement, and more. Nobles vied for Breguet watches, and Marie Antoinette was said to be no exception.

Although Chappe was a Breguet with an age gap as wide as that between a father and grandson, upon receiving Chappe’s request, he immediately created and provided a model of the new mechanism. Based on this model, Chappe assembled the device at the experimental site and proceeded to the official communication experiment.

The experiment involved constructing apparatus at three locations — Belleville, Équan, and Saint-Martin-de-Tertre — northwest of Paris, connecting them over a distance of approximately 25 km. At 16:26 on July 1, 1973, the experiment commenced in the presence of a government commission comprising scientists and legal experts. The lever at the Belleville communications station, where Chappe was stationed, began to move. Shortly after, the lever at Écain, 15 km away, started moving. Though invisible from there, the signal traveled another 10 km to de Tertre. After approximately 11 minutes, the following message was transmitted:

“Donu (a committee member) has arrived here. And he said the National Convention has just granted the Committee of Public Safety the authority to approve the documents of the delegates.“

Next, a message was sent from de Tertulle: ”The people living in this beautiful country deserve to enjoy freedom under the law of the esteemed National Convention.”

Both messages were confirmed by the commissioners as having been sent without error, and the success of the experiment was reported to the Assembly two weeks later.

First major achievement

Thus, the first section of the optical telegraph system—a 200-kilometer communication line connecting Paris and Lille—was laid over the course of a year. For the revolutionary French government, under attack from surrounding nations, Lille, bordering Belgium, was a crucial stronghold.

About 135 km west of Lille lay the Condé fortress, deeply entrenched within Belgian territory. At that time, this vital fortress had fallen into the hands of Austrian and Prussian forces, and fierce battles were being fought.

In August 1974, documents just received via optical telegraphy were read aloud from the parliamentary podium: “A report has just arrived via optical telegraphy. Condé has been recaptured by the Republic.”

A murmur swept through the chamber, followed by shouts of “Long live the Republic!” and thunderous applause. Once the noise subsided somewhat, it was announced, “The enemy surrendered at 6 o’clock this morning.” Cheers and applause erupted again, continuing for some time.

The assembly immediately resolved to call Condé the “Free North” and the victorious soldiers “benefactors of the motherland.” This decision was instantly sent to Lille via optical telegraphy. Shortly after, Chappe reported, “Mr. President, we have just received confirmation that the message has reached Lille.”

This achievement cemented the Assembly’s appreciation for optical telegraphy. Information that had previously taken days now arrived in an instant, and it could be exchanged bidirectionally!

The government decided to install it nationwide. And within just over five years, a communication network of optical telegraphy systems, stretching 1,426 km in total length, suddenly appeared across all of France.

Eventually, Napoleon, who seized power, also recognized the value of optical telegraphy, expanded the communication network further, and made extensive use of it. Its utilization may have been one factor contributing to his victories in numerous wars.

Having secured Italy, Napoleon, aware of the difficulties posed by the Alps, instructed, “If possible, I wish to have Milan and Paris connected within fifteen days.” The line between Turin and Milan, crossing high ground at 2,000 meters, took two years to complete.

The Agony and Death of Chappe

Optical telegraphy achieved great success, but Claude Chappe’s path was far from smooth sailing. Many adversaries, jealous of Chappe’s success, emerged. Among them was Breguet, who had once been his supporter.

Breguet, who had deep ties with the nobility, fled to his homeland of Switzerland after the Revolution, sensing danger to his life. Eventually, with the execution of Robespierre, the Reign of Terror subsided. When Breguet set foot on French soil once more, an optical telegraphy network connecting all of France had spread across the land.

Seeing this, Breguet felt uneasy. He had designed this device, yet the young upstart Claude Chappe was being hailed as the hero.

So he teamed up with a Spaniard who had devised a similar communication device and pitched it to the government, aiming to oust Chappe.

However, Breguet’s feelings were based on a misunderstanding. While the mechanism Breguet created certainly functioned well, the true essence of the optical telegraphy system lay in the rules and operational mechanisms that governed the entire system. It was Chappe who had laid the foundation for all of these.

Ultimately, Chappe’s system spread across the entire country. Yet, numerous others also claimed Chappe had stolen their ideas. Psychologically cornered, Chappe took his own life by jumping. January 23, 1805. He passed away without ever witnessing the communication network that would later spread throughout all of France.

The Achievements of Claude Chappe

As mentioned earlier, Claude Chappe’s achievement lies in establishing the protocols and operational rules for the entire optical telegraphy system, refining it into a mechanism nearly identical to the Internet.

Within the communication network radiating out from Paris and branching out in all directions, messages were assigned address information to ensure they reached their intended recipients. At branching relay stations, messages were routed to their destinations based on this address information. This function corresponds to the role of routers supporting today’s internet network.

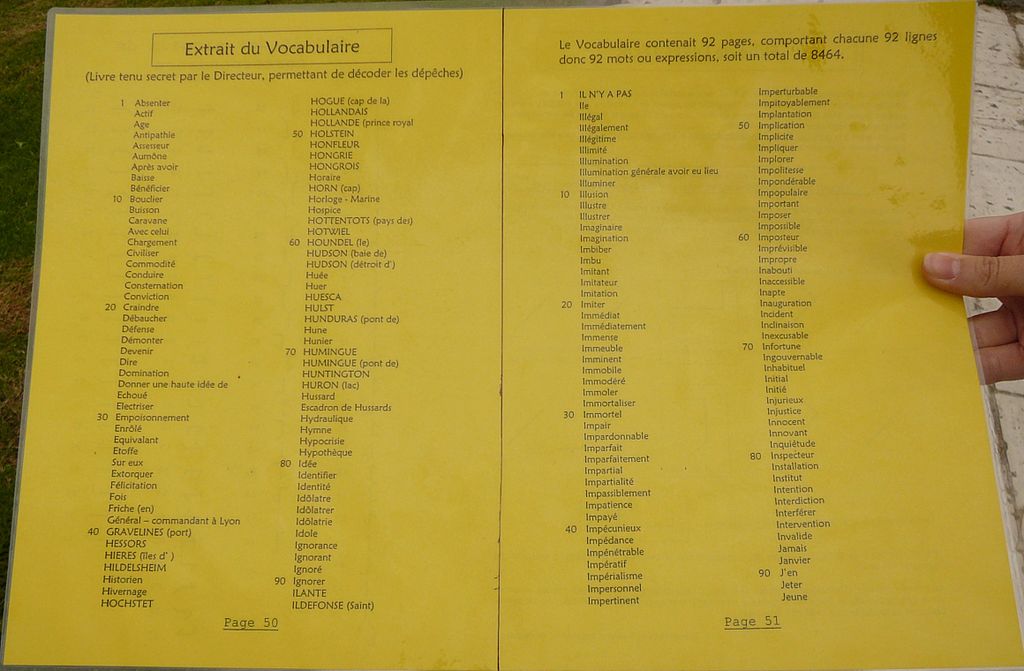

Furthermore, since the movement of the semaphore arms was visible to anyone, sending information in plain text risked interception of official documents. Therefore, documents were encrypted by replacing words with numbers using a dedicated code book before transmission. This code was not known to the operators at the relay stations. They simply operated the semaphore arms according to the rules.

Optical telegraphy enabled two-way communication, meaning information could arrive from both ends of the network simultaneously. To handle such collisions, messages were assigned priority codes, which determined precedence. When priorities were equal, messages originating from Paris (the network’s starting point) took precedence. Modern internet technology incorporates similar mechanisms at its lower layers.

In addition to these features, it also incorporated error correction mechanisms, making the entire optical telegraphy system essentially the precursor to the internet.

This system operated through the labor of people working inside the towers.

Operator’s Job

Initially, operators were recruited from veterans, but gradually, unmarried or childless men residing near the relay stations were hired instead. (You can probably guess why.)

Operators worked in two-person shifts. The operator who spent the night in the lower level of the relay station would eat breakfast before dawn, ascend to the semaphore operating room, and take his position. As the surroundings brightened and the semaphores of both relay stations became visible, the operator’s work began.

Given the responsibility of handling official documents, leaving one’s post except during breaks was forbidden, and fines were imposed on those who violated the rules.

As noon approached, the relieving operator would arrive, allowing the first operator to finish his shift and return home. From then on, the other operator would handle the work until sunset, spend the night at the relay station, and continue the job until noon the following day. Good work!

* 中野明著『腕木通信―ナポレオンが見たインターネットの夜明け』

The Modern Internet

Teachers must narrate such stories as vividly as possible. Students themselves must feel as though they are performing a demanding yet responsible task within the confines of a narrow tower, witness thrilling official experiments alongside Chappe, share in the fervor of the assembly hall during the recapture of Condé’s fortress, smile wryly at Napoleon’s tyrannical ways, and empathize with Chappe’s troubled state of mind.

Beyond that, the stories surrounding optical telegraphy are full of fascinating episodes. Optical telegraphy boasted transmission speeds far exceeding the speed of sound. It was vulnerable to fog. The semaphore arms at Paris’s main station stood atop the roof of the Louvre Palace we know so well. Even then, sophisticated cybercrimes were occurring, and stories unfolded where unexpected flaws exposed criminal secrets, leading to the apprehension of the perpetrators.

Once the students have entered the story’s world, the teacher draws a network resembling the internet on the blackboard. He explains that the nodes at the intersections of the lines correspond to relay stations in the optical telegraphy system, and that computers have taken over this work from humans. Signals of 0s and 1s travel along the lines connecting the nodes, using the exact same mechanism seen in the telegraph experiment.

In this way, the students dive into the technology of the internet through vivid imagery drawn from their own experiences.

From here, I’ll briefly explain how the internet works on the blackboard. Address numbers are assigned to the endpoints of the internet network, and relay stations have a general understanding of this structure.

The sender of information attaches destination and sender information to the main data packet and sends it out onto the network. The router that receives it checks the destination and selects the appropriate route. This process repeats multiple times until the information reaches its intended recipient. It’s the same job the operator inside the tower used to do. And that’s the simple mechanism of email.

Large pieces of information are divided into smaller chunks, called packets, and sent out in groups. This allows multiple users to share the same path, preventing any single communication from monopolizing it indefinitely.

Sometimes packets arrive out of order. However, each packet is assigned a sequence number when sent. The receiver can reassemble them in the correct order to retrieve the original information.

Internet terminals may be connected to computers called servers, which have large amounts of memory (students already know how this works!). Examples include web page servers.

When Person A wants to view a specific webpage, they send a request signal to that webpage’s address. The server receiving this request reads the specified webpage’s information from its memory and sends it back, addressed to Person A’s location. Person A receives this data, assembles it, and displays it on their computer screen to view.

Bulletin board systems and SNS platforms can be described as extending this mechanism by allowing third parties to write information into specific locations within the server’s memory.

If time permits, we could discuss various other services as well. It would also be good to explain things by answering questions raised by the students. However, the basics covered here are sufficient. After all, they are just about to start using the actual internet.

Simulated Internet Workshop

To conclude, I’ll share the ideal we envisioned during the dawn of the internet and discuss how it has evolved into the present.

Here, we clear the desks, arrange the chairs in a circle, and sit facing each other. Then, I take out a soft ball and say:

“Over these past ten days, you worked together to complete a large computing machine. It was an automated machine that was just one step away from becoming a computer. And today, we learned that the structure of the internet already existed during the time of the French Revolution. The work done by the people laboring inside those stone relay station towers is now handled by small computers. Thanks to this internet technology, we can instantly exchange information with people all over the world.”

“This circle represents the Earth. We are people from various countries living on this round Earth. Now, one by one, please say the name of your favorite country, making sure not to repeat any.”

The students call out the names of various countries. When they finish, he points to the ball and says:

“This ball represents a packet flying through the internet. Now, I’ll entrust my country’s introduction to this packet and toss this ball to someone from a country whose gaze I meet. Please catch it. That person will then repeat what I did.”

Then, holding up the ball, they deliver their message.

“I am Japanese. The flower representing my country is the cherry blossom.”

They throw the packet to the person they made eye contact with. The person who catches it repeats the process.

Sometimes the receiver drops the ball, but if they try to pick it up, I stop them.

“Right now, an error occurred and the packet didn’t arrive. When an error happens, we resend the same information, right?”

This is how I imagine various words traveling across the Earth.

After it makes a full round, I retrieve the ball and say:

“This is the kind of wonderful world the pioneers of the Internet dreamed of. A free, barrier-free, equal, and democratic online space would emerge. But reality didn’t turn out that way. In fact, situations opposite to what was aimed for have even arisen. We must think about why this is so and how we can overcome it, and then take action.”

Then, share several examples and, if possible, hold a small discussion. (For the examples, please refer to the reference materials.)

There will be various exchanges, but I think it’s good to keep the following key points in mind.

“When automobiles were invented, there were no traffic laws that took cars into account. After many traffic accident victims emerged, people learned, and by creating rules, they were able to safely operate vehicles. To drive a car, you must attend a driving school, learn safe driving methods and traffic laws, and prove you have the ability to comply with them.”

“The current internet resembles the era when cars were running wild. Even when people’s privacy and rights are threatened, the means to control the situation are woefully inadequate.”

“You will likely use the internet daily, but you must understand that the online world is imperfect and prepare for emergencies. The best preparation is to find a trustworthy person well-versed in the internet and computers. If something happens, don’t try to solve it yourself; consult that person immediately.“

”As we’ve seen, computer technology has a high potential to interfere with human freedom. Online, this is done subtly. Using techniques like profiling and microtargeting, it influences people’s subconscious to control their behavior patterns and ways of thinking.”

“Japan’s Constitution guarantees the freedom of thought, belief, and conscience for individuals. Constitutionalism is the principle that seeks to protect vulnerable individuals from the power of the state and other large entities by binding them with laws.”

“During wartime, there was an era when merely voicing opposition to the war led to arrest by the police and torture.

Constitutionalism seeks to halt such abuses of power through the force of law and protect liberty of conscience. However, today, the internet has greatly increased the danger of people’s inner thoughts being manipulated.

In modern Western countries and Japan, the major power infringing on people’s freedom of thought is corporations. Under these new circumstances, discussions are underway to establish a new ‘Digital Constitutionalism’ that expands the scope of constitutionalism to protect individual freedom of thought.

Unlike automobiles, regulating internet technology — which spreads across borders and possesses an incomparably greater level of complexity — is extremely difficult. That is precisely why I want you all to take an interest in such major debates while venturing out onto the vast ocean of the internet.”

In conclusion

Up to this point, we have progressed our learning about the internet without using the actual internet at all. If teachers take this class seriously, students will understand its value. In fact, one student said:

“I think it was good that we could learn this way without touching a computer at all.”

We strongly urge teachers to take ample time before connecting PCs to the internet to focus on how each individual in society creates value within their own sphere and how they exchange that value with others.

Just reflecting on activities like creating stories, birthday treats, bread baking, home building, vegetable growing, foreign language pen pals, Christmas ornaments, and Waldorf activities—how richly we find value in them!

Teachers must take it as self-evident that the internet is a technology for exchanging the value created by such human beings.

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Seesaw Logic Elements

- Clock and Memory

- The Origin of the Relay and the Telegraph Apparatus

- About the sequencer

- About the Battery Checker(Currently being produced)

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Integer type

- Floating-point type

- Character and String Types

- Pointer type

- Arrays

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)