Arrays

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

Introduction

Through studying various data models, you’ve likely gained an understanding of how computers manipulate information like numbers, strings, images, and audio. All the applications people conveniently use daily on personal computers are realized by combining these fundamental technologies.

Among such applications, we previously examined the mechanisms behind one of the most popular ones—word processors—in the string-type section. Here, we will explore how another representative application, spreadsheet software, operates.

Imprint the rhythm onto memory

In the section on learning data models titled “Bits, Bytes, Words, and Memory Map Images”, we saw that memory is a one-dimensional grid arranged linearly.

______________________ …

Humans have designed this simple grid to build various data models. Arrays are also one such data model.

Let’s divide this one-dimensional grid into segments at regular intervals. It looks like this.

1__2__3__4__5__6__7__8 …

By considering the three memories as a single column and viewing each set of three as forming a column of equal size, we can treat them as a two-dimensional table with three columns, as shown below.

1__

2__

3__

4__

5__

6__

7__

8 …

What happened was that humans assigned meaning to the arrangement of memory. That’s all.

This way, we can easily create a memory structure well-suited for handling tabular information like this. This mechanism of partitioning memory into rows and columns, creating a row-column structure, and enabling information to be placed in each partition is called an array.

Arrays

Information for each individual section can be specified by row and column, allowing it to be handled like a table. This is essentially how the vast expanse of memory was subdivided into sections to make it easier to handle according to human thought processes.

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Row 1, Column A | Row 1, Column B | Row 1, Column C |

| 2 | Row 2, Column A | Row 2, Column B | Row 2, Column C |

| 3 | Row 3, Column A | Row 3, Column B | Row 3, Column C |

| 4 | Row 4, Column A | Row 4, Column B | Row 4, Column C |

| 5 | Row 5, Column A | Row 5, Column B | Row 5, Column C |

| 6 | Row 6, Column A | Row 6, Column B | Row 6, Column C |

| 7 | Row 7, Column A | Row 7, Column B | Row 7, Column C |

| 8 | Row 8, Column A | … | |

This can be further developed.

- By further dividing a two-dimensional array into segments at fixed intervals, a three-dimensional array is created.

- By repeating the same process, you can also easily create multidimensional arrays.

From a one-dimensional grid arranged in a straight line, we can create arrays of any dimension, no matter how large. Human thought is truly magnificent!

Here, it would be interesting to have students draw images of one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional arrays on the blackboard or paper, then ask if they can imagine arrays of four or more dimensions. Even if imagining them is difficult, we also confirm that it is possible to express them as arrays.

Spreadsheet Programs and Arrays

Now, for arrays created this way, the data size per element must be fixed. This is because memory is partitioned into units of a specific size.

For a table containing only integers, this remains perfectly practical. But how should we handle data with variable lengths, like strings, in an array? What if we want to store diverse information—numbers, characters, formulas—in each element of the table?

One approach is to allocate memory with extra space for each element, sized for the largest possible element that might be stored. However, this method results in significant memory waste.

This is where pointer types come into play once again. By creating an array using pointer type data, you can handle any type of information while keeping the data size per element constant.

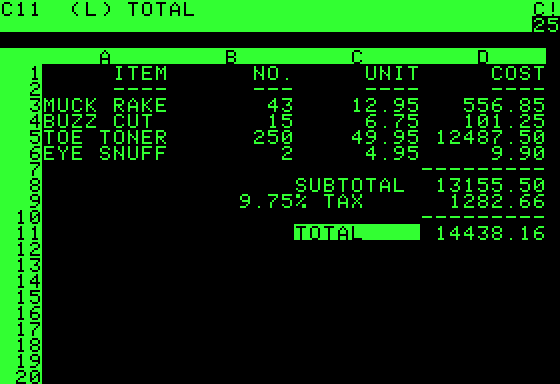

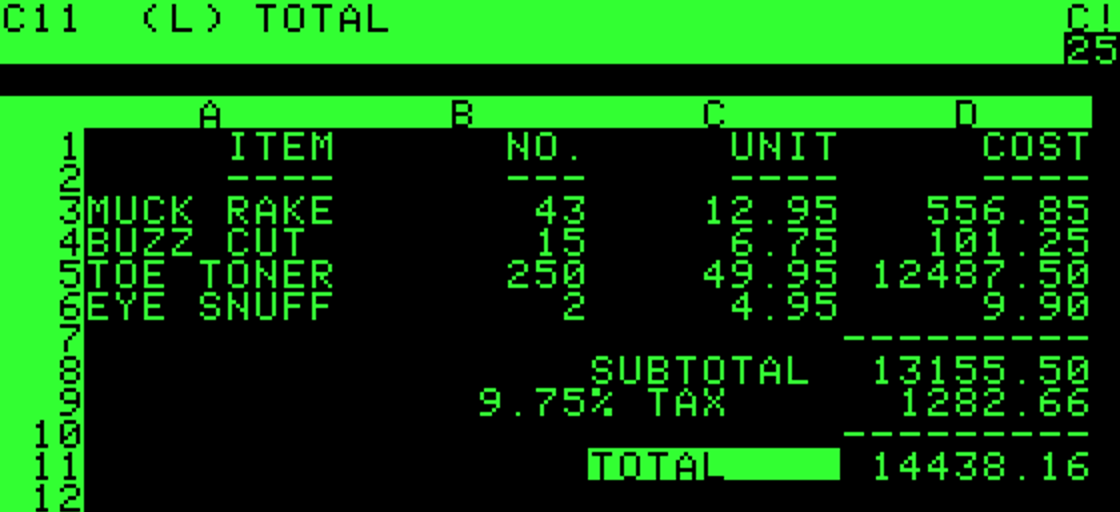

Spreadsheet programs are convenient applications built using this mechanism. The example below shows a simple ledger created using a spreadsheet program. You can see the use of a two-dimensional array mechanism.

| A | B | C | D | E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pointer A1 | Pointer B1 | Pointer C1 | Pointer D1 | Pointer E1 | |

| 2 | Pointer A2 | Pointer B2 | Pointer C2 | Pointer D2 | Pointer E2 | |

| 3 | Pointer A3 | Pointer B3 | Pointer C3 | Pointer D3 | Pointer E3 | |

| 4 | Pointer A4 | Pointer B4 | Pointer C4 | Pointer D4 | Pointer E4 | |

| 5 | Pointer A5 | Pointer B5 | Pointer C5 | Pointer D5 | Pointer E5 |

Each row from 1 to 5 has columns from A to E, with pointer-type information stored in each memory location. By using these pointers to reference data of any type, we can freely modify the contents of the table.

Let’s set the following information in the table created with this array. Instantly, the summary tables we use daily appear. What is displayed is the content of the information placed at the address pointed to by each compartment’s pointer.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Date | Expense item | Unit price | Quantity | Subtotal | Notes |

| 2 | March 3 | Popcorn | 100 | 5 | C2×D2 | E2:It displays as 500 on the screen. |

| 3 | March 5 | Juice | 300 | 3 | C3×D3 | E3:It displays as 900 on the screen. |

| 4 | March 6 | Cake | 400 | 2 | C4×D4 | E4:It displays as 800 on the screen. |

| 5 | Total | SUM E2:E4 | E5:The sum of E2 and E4, 2,200, is displayed on the screen. |

Green in the table indicates string data, blue indicates numeric data, and red indicates formula information. When a spreadsheet program draws this table on the screen from memory, it performs the following operations based on the type of information stored in each compartment (called a cell in spreadsheet programs):

- String type: From a memory block containing glyph patterns, sequentially copy the glyph pattern corresponding to the character code of the string to the desired position in the frame buffer (video memory).

- Numeric type: (1) Convert binary notation to binary-coded decimal (BCD). (2) Convert each digit’s numerical value to a character code (add the offset value from the corresponding numeric code’s ID value to the number). (3) Display the resulting string on the screen using the same rules as the string type.

- Formulas (called functions in spreadsheet programs): Interpret formulas, perform calculations between cells based on instructions, and display the results on the screen according to numerical procedures.

In addition, spreadsheet programs perform tasks such as drawing gridlines on the screen to give tables a proper layout. They also provide mechanisms allowing users to specify the position of each cell for manual editing, and interpret input instructions to convert data into text or numeric formats before placing it into cells.

After explaining these concepts to some extent, have the students actually use a spreadsheet to create a table. The teacher should advise them to work while visualizing what is happening behind the scenes as they build the table.

Behind what appears to be a very simple spreadsheet program, a tremendous number of processes are actually being executed. Make sure the students understand that the ability for users to utilize spreadsheet programs without stress is due to the immense processing speed of modern CPUs, which can handle an enormous number of processes per unit of time.

The History of Spreadsheet Programs

Once you have a basic understanding of arrays and spreadsheet programs, it’s a good idea to learn about the history of spreadsheet programs.

The world’s first widely adopted spreadsheet software is said to be VisiCalc, developed as a program for Apple’s Apple II personal computer. It was such a groundbreaking software that in 1980, 70% of Apple II sales were driven by the demand to run VisiCalc.*1

This program transformed computers, which had been mere “toys” for enthusiasts, into versatile tools usable in business.

Dan Bricklin, one of the co-creators of VisiCalc, studied electrical engineering and computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was developing word processors at Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). On a whim, he quit his job and enrolled at Harvard Business School to study business administration.

One day, he was attending a lecture on various financial models. The professor drew a grid on the blackboard, placed numerical values representing each component of finance within it, and explained how these values changed based on the equations defining each financial model.

Dan, who understood computer architecture and could vividly imagine the numbers represented in memory, had a flash of inspiration.

Yes. Of course, it was the thought: “We could just perform these operations on the blackboard directly in computer memory!”

Dan and his colleagues wrote a program that replaced the operations performed on the blackboard with information manipulation on arrays, displaying the results on a computer screen. Called “Dan Bricklin’s Demo Program,” it ran on the Apple II in the spring of 1978.

Dan and his team continued refining the program, and the following year, they demonstrated the program—which they named VisiCalc—at several computer trade shows. This proved to be a tremendous success.

Because it was a program exclusively for the Apple II, VisiCalc instantly became the killer app that cemented the Apple II’s dominance as the go-to personal computer for business use. While the exact source is unclear, it’s said that as much as 70% of Apple II sales in 1980 were attributed to VisiCalc.

This marked the birth of VisiCalc and the beginning of spreadsheet programs. What mattered to people was not the marvel of the computer hardware itself, but what kind of programs could run on that computer.

In closing

By linking it to spreadsheet programs, students will gain a vivid understanding of the nature of arrays. Simultaneously, they will grasp how information on arrays is manipulated behind the scenes in spreadsheet programs and projected onto the screen. This approach to learning is the very essence of studying data models.

Various computer software is created by humans organizing how they manipulate their own thoughts, then replacing that with program definitions of data structures and their operation algorithms.

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Seesaw Logic Elements

- Clock and Memory

- The Origin of the Relay and the Telegraph Apparatus

- About the sequencer

- About the Battery Checker(Currently being produced)

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Integer type

- Floating-point type

- Character and String Types

- Pointer type

- Arrays

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

コメント