Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

- Introduction

- Class Flow

- Daily Life and Logical Operations

- Relay Observation and Wiring Practice

- Master the relationship between circuit diagrams and actual wiring

- Practical training using a workbench

- AND circuits and OR circuits

- Positive Feedback and Negative Feedback—Memory and Clock

- The Mechanism of Telegraphs—Fundamentals of Transmission

- Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Relay Savings: Staircase Lighting System XOR Circuit

- Regarding Group Work

- From full-adders to multi-digit adders

- From Calculator to Computer

- Overview of the Computer System

- Fundamentals of Information Processing

- Internet

- In closing

Introduction

This article provides a detailed explanation of the lesson plan “Construction of a Multi-Digit Adder Using Relays, Already Widely Practiced,” as outlined in “Forming the Framework for an ICT Curriculum in Waldorf/Steiner Education.”

This two-week, ten-session main lesson, which I have conducted annually since 2013 at the end of the ninth grade at Yokohama Steiner School, focuses on building a multi-digit adding machine. Its purpose is to provide an understanding of computer technology and the fundamentals of the internet.

Here, we introduce relay-based adder circuits and sequencers that enable automatic computation when connected to them as the best teaching materials for students to grasp the fundamental principles of computer operation through their own thinking and intuition.

For this class, I designed a simple 8 x 3-bit sequencer. Through my teaching practice so far, I have confirmed that this serves as a versatile teaching tool—applicable for explaining memory, evoking the concept of punch cards, illustrating display devices, and more.

You can also view a demonstration video of this device within this material.

For details on how this lesson plan was developed, please refer to the document below.

Class Flow

This series of lessons is implemented in the 9th grade as a response to the situation in Japanese society, where ICT environments are ubiquitous, causing students’ interests to quickly shift toward them, and to the possibility that students may begin using PCs starting in the 10th grade.

By carefully pacing the lessons, we achieved manageable learning even for 9th graders, though I feel the content is slightly too advanced for their age. If the country or region’s circumstances allow, it would be better to delay PC exposure and implement this course in 10th grade or later.

The flow of the classes I conduct is as follows.

Day |

Theme |

Content |

|---|---|---|

1 |

Introduction |

|

2 |

Practical Exercise on Seesaw Logic Circuits |

|

3 |

Relay Logic Circuit Practice 1 |

|

4 |

Relay Logic Circuit Practice 2 Memory circuit and clock circuit using a feedback circuit |

|

5 |

Telegraph Technology From Logic to Computation—The Foundations of the Adder |

|

6 |

Half-adder Carry Concept |

|

7 |

From Half Adder to Full Adder |

|

8 |

Implementation of a multi-digit adder Automatic calculation |

|

9 |

From Calculator to Computer |

|

10 |

Internet Technology and Literacy |

|

Daily Life and Logical Operations

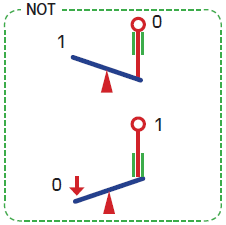

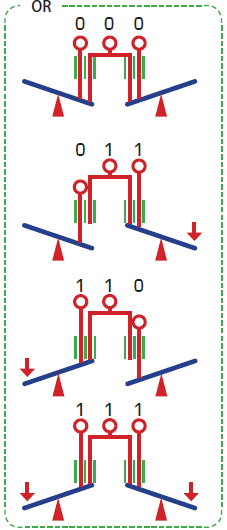

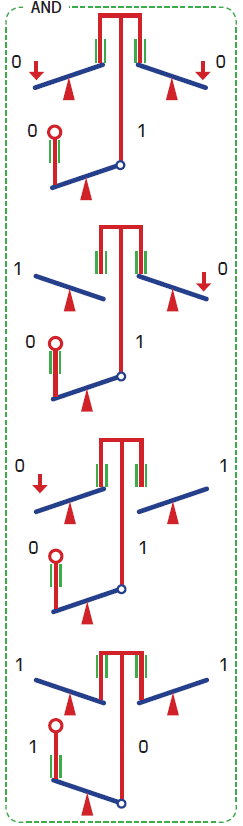

We learn that all digital computers are built using just two types of logic: AND and NOT, or OR and NOT. We begin this learning journey by recognizing that we use such logic in our daily lives.

We start with examples like combining trip conditions with AND logic or choosing tonight’s side dishes with OR logic, then guide you to how such logic is applied within machines.

For example, when an elevator is moving up or down, it is advisable to illustrate that the safety mechanisms are functioning correctly by combining conditions such as the doors being closed, the weight not exceeding limits, and no detection of shaking from earthquakes, etc., using an AND logic. In doing so, organize this information into a truth table using ○ and ×.

So, what if we used this AND logic for the circuit of the buzzer button used to notify the driver when you want to get off at the next bus stop? Using such humor allows students to vividly connect the world of logic with their own everyday experiences. Of course, this circuit must be built using OR logic.

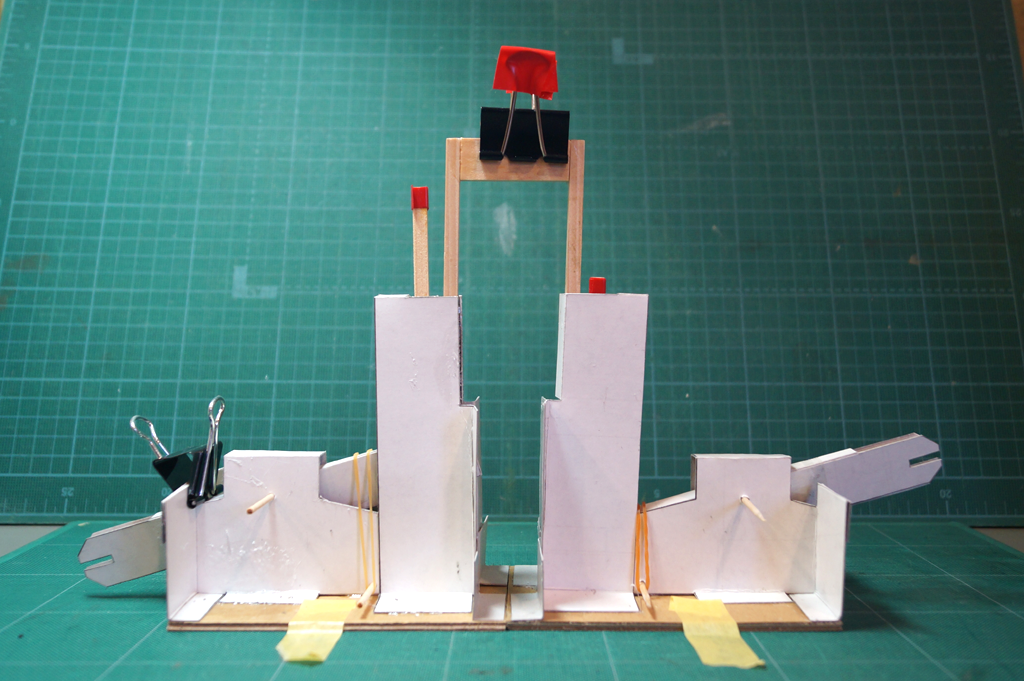

After this introduction, when looking for examples of NOT logic in everyday life, I use a seesaw as an example. Then, using an actual seesaw, we test the mechanisms of NOT, OR, and AND.

This hands-on activity demonstrates that logic can be implemented without using electrical mechanisms. It also visualizes the implementation of logic, allowing students to experience its operation firsthand.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that while creating OR operations with a seesaw is straightforward, creating AND operations is extremely difficult. By guiding students to observe this and then showing how De Morgan’s laws yield solutions, we can highlight that computers represent a technology with a directionality opposite to that of technologies like the steam engine, which evolved from observation.

Details on seesaw logic using thick paper are explained on the following page.

As an example of AND logic applied in safety devices, I tell my students about my part-time job at an automobile factory during my student days. There was a device for spot welding large molded parts made by pressing metal sheets. After setting the parts in place and pressing a large push button, multiple welding rods would descend before your eyes, welding the parts while pressing them together.

The machine required not one, but two buttons to be pressed simultaneously to activate. I ask my students why this was necessary. “What if you noticed the parts were misaligned immediately after pressing the button? What if one hand was free at that moment?”

Yes, you might have ended up with a big hole in your hand. It’s not a bad thing to appeal to students’ imagination in a way that involves pain.

Relay Observation and Wiring Practice

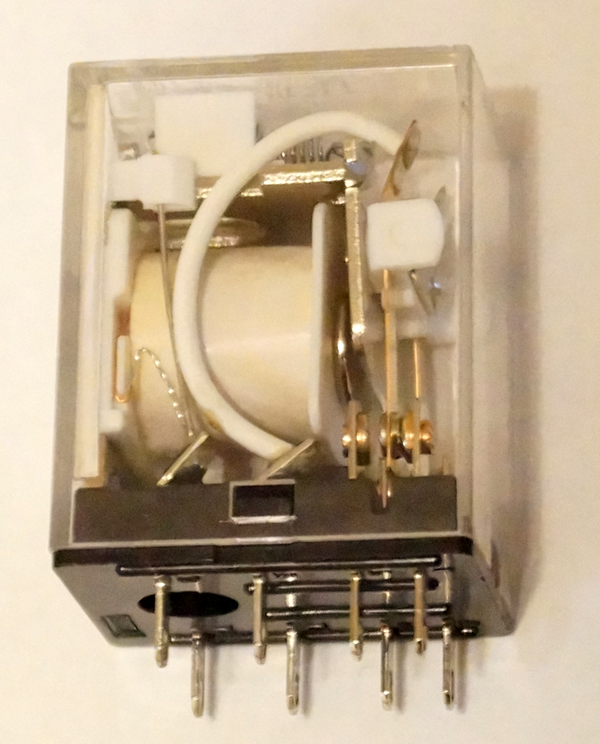

After experiencing the basic logic devices using seesaws, we will now introduce electromagnetic switches called relays. We will use these to build the multi-digit adder we are about to tackle. It is essential that students have completed the electromagnetism unit and possess knowledge of circuits and electromagnets.

First, distribute one relay to each student and observe.

The relay to prepare should be a control relay rated for DC12V with two circuits, housed in a transparent case measuring 28mm x 21.5mm at the base. This is appropriate for the following reasons:

- The transparent case allows visual observation of the mechanism and operation.

- It produces a relatively loud operating sound, conveying a tangible sense of movement. This is particularly impressive during automatic calculations, as it creates a complex rhythm alongside the computation, making it useful for explaining computer music.

- The coil terminal width matches that of a 006P type 9V battery terminal, allowing direct battery contact for convenient operation observation.

- It’s convenient that a 006P type 9V alkaline battery can power a circuit equivalent to a full adder.

- It is relatively inexpensive and readily available.

Master the relationship between circuit diagrams and actual wiring

At this stage, students do not yet understand the relationship between circuit diagrams and actual wiring, so we first allow time for them to become familiar with it. By carefully progressing through this step, understanding the work content becomes easier, and the entire lesson proceeds smoothly.

I am proceeding with this using the following steps:

- Prepare a worksheet with the buffer logic circuit diagram and component diagrams (photos) side-by-side, and have students manually draw the wiring connections. Strictly enforce tracing the circuit starting from the battery’s positive terminal.

- Perform the actual wiring while referring to the completed wiring diagram.

- Once complete, create a truth table to verify that it operates as designed.

- Try reconnecting the NO (Normally Open) wiring to the NC (Normally Closed) terminals. Verify that it now functions as a NOT circuit.

The above practical training can be conducted if individual parts are provided, so it is desirable that every student, without exception, be able to experience it.

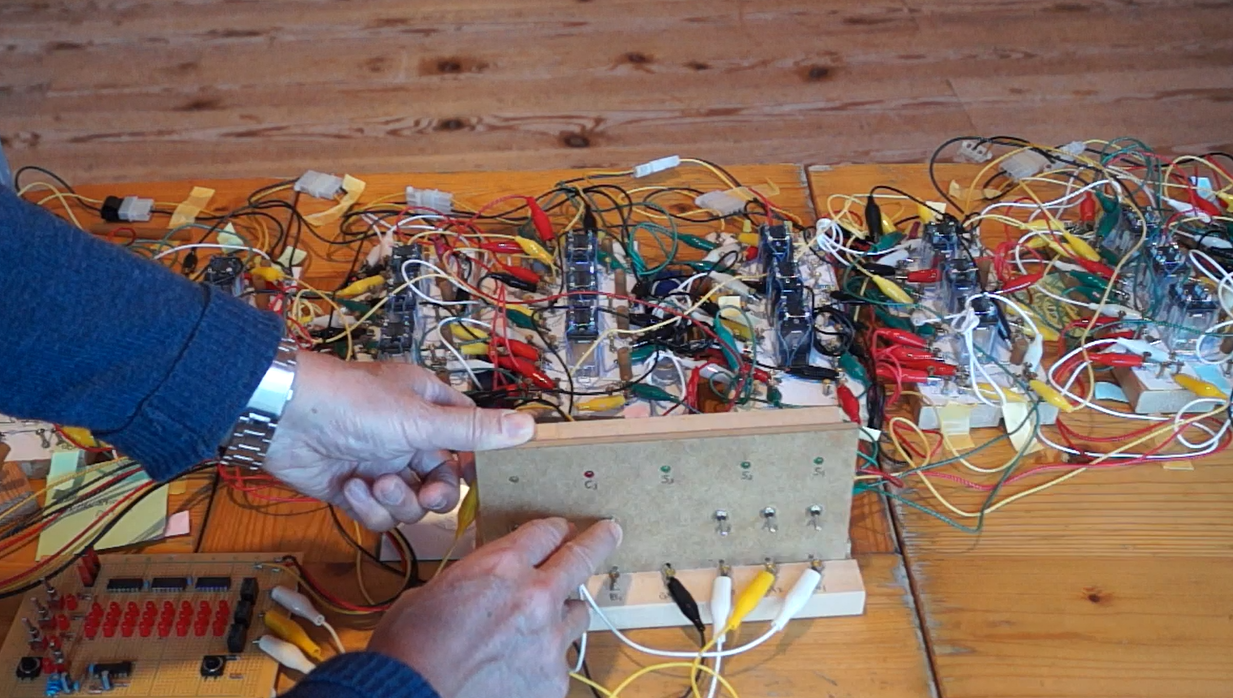

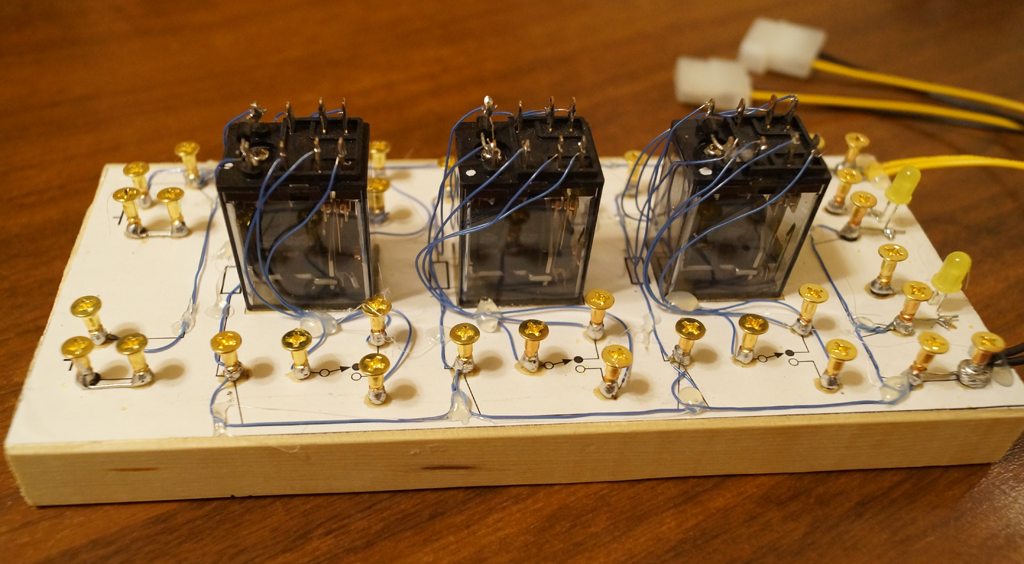

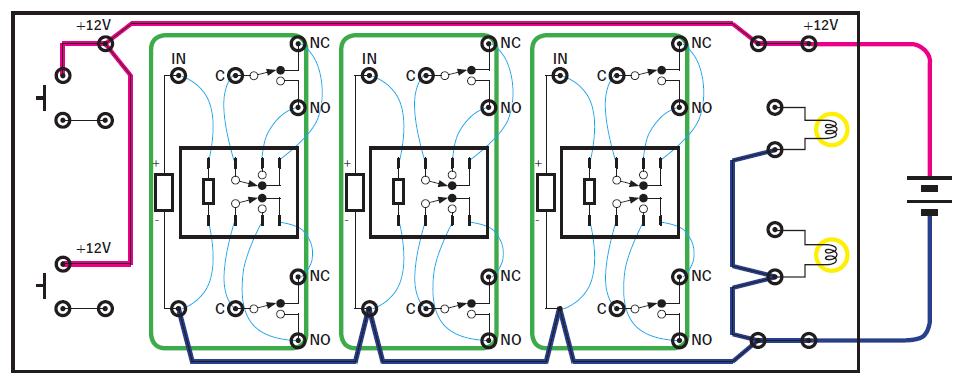

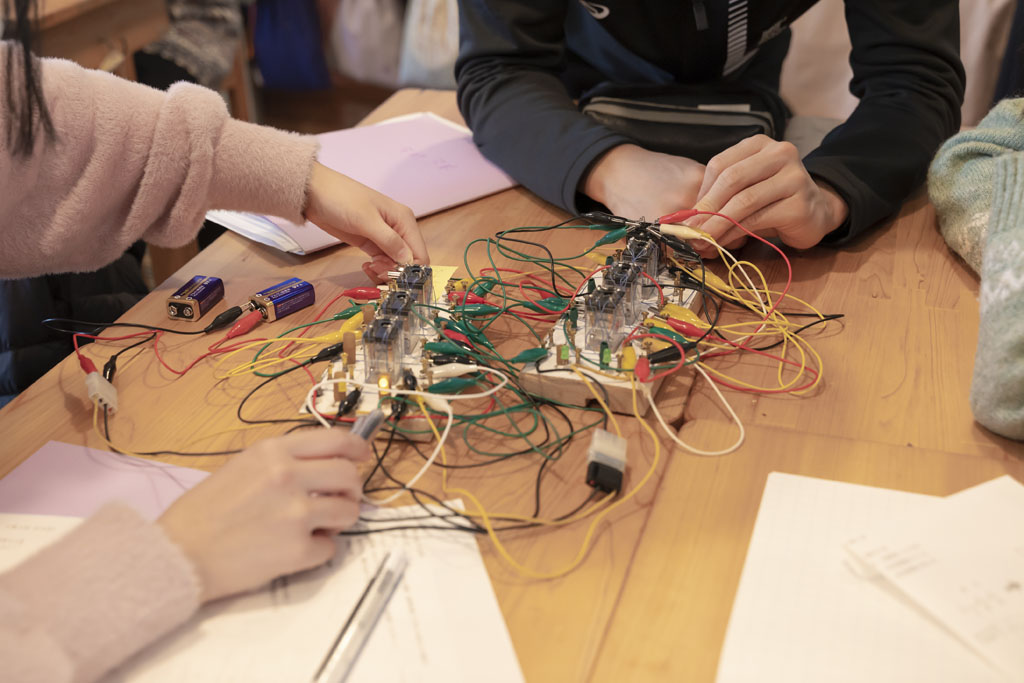

Practical training using a workbench

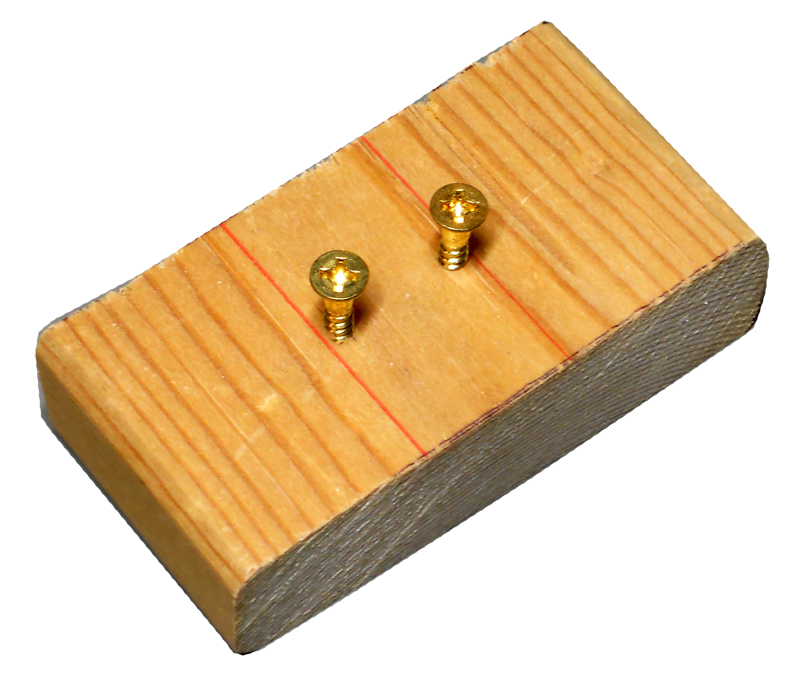

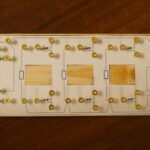

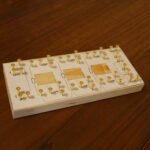

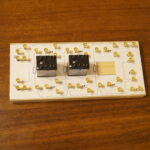

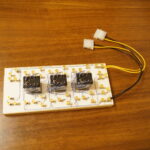

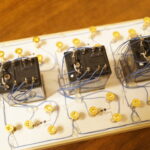

After understanding the relationship between circuit diagrams and actual wiring through aerial wiring practice, you will proceed with workbench-based tasks. The workbench I built incorporates three relays, two switches, and two resistor-integrated LED lamps (rated voltage 12V).

The half-adder ultimately built on the workbench consists of two relays, but three relays are mounted as spares in case one fails or a wire disconnects. Additionally, these relays are used for the OR circuit that combines carries when configuring two half-adders as a full-adder (described later).

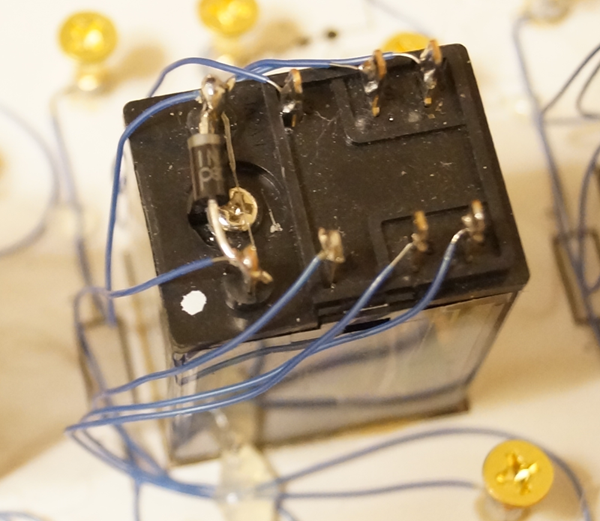

The workbench is a simple setup where all relay terminals are simply wired to brass screw nails using wrapping wire. However, one side of the switch—composed of two screw nails—is pre-wired to the battery’s positive terminal, while the LED cathode and one side of the relay coil are pre-wired to the battery’s negative terminal. This reduces the amount of wiring work required by students.

Additionally, while the 006P type battery is used for regular practice, during the final stage of assembling the multi-digit adder, all full adders are connected in a daisy chain configuration and linked to a stabilized power supply. Therefore, a pair of male and female power connectors is installed. Therefore, a pair of male and female power connectors is installed. I cut a peripheral connector extension cable for HDDs in half and use it.

Be sure to install a surge voltage suppression diode (such as a 1N4007) on the relay coil. Failure to do so will cause the device to malfunction when connecting the automatic calculation sequencer circuit. This is also a precaution for the rare child who is sensitive to electricity.

We will wire the circuit using cables with alligator clips attached to these screw terminals. I find working with alligator clips is easier than soldering, yet requires more concentration than using banana plugs, making it well-suited for this learning activity.

AND circuits and OR circuits

Next, we should build the basic logic circuits that make up a computer—AND and OR circuits—using relays.

Before that, however, I draw a closed circuit on the blackboard connecting a battery and a light bulb. I then have the students think about how to place two switches here to create an AND circuit. This should be relatively easy to figure out. The OR circuit is a bit more challenging, but some students will still figure it out. Then, have them realize that these represent the difference between series and parallel connections.

Once students understand that we will use a mechanism (relay) that enables these switches to be operated by electromagnets to build various circuits, we will proceed to the practical exercise.

Draw circuit diagrams for AND circuits and OR circuits using relays on the blackboard, and then build these circuits on the workbench according to the diagrams. When doing so, the teacher must guide the students while paying attention to the following points:

- First, confirm which wiring is already connected on the workbench.

- Confirm how the switches, relay terminals, LEDs, and power supply are arranged on the workbench.

- Starting from the positive terminal of the battery, trace the circuit flow and connect the wires toward the negative terminal.

- Finally, connect the battery, test all switch combinations, and record the relationship with the light bulb’s ON/OFF state in a truth table. (Of course.)

With this, the students were able to build all the circuits—AND, OR, NOT, and Buffer—using relays. This alone was a fun and rewarding experience for them.

Positive Feedback and Negative Feedback—Memory and Clock

We won’t start building the computer right away. Before that, we’ll learn through hands-on practice how memory works and how clock pulses are generated. This will lay the groundwork for gaining a vivid understanding of the computer system as a whole.

The perspective of polarity is extremely useful for understanding these concepts. We use negative feedback and positive feedback.

The details are explained in the following separate sections.

The Mechanism of Telegraphs—Fundamentals of Transmission

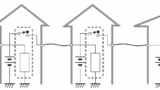

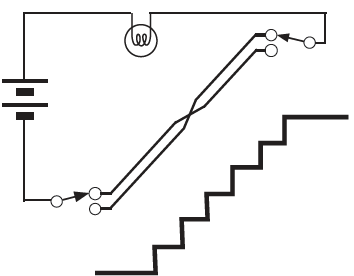

Here we introduce another important theme. We explain telegraph technology, the foundation of electrical transmission technology, and conduct actual experiments.

It’s best to introduce this by exploring the historical background: “Why did a device that should be called an electromagnetic switch come to be called a relay?”

We’ll cover well-known Morse code, such as SOS, and explain telegraph technology—a device that sends information over long distances by varying the length of the switch’s ON/OFF states. The transmitter has a key switch; the electrical power sent from this switch travels through wires to the receiver, causing a buzzer to sound.

However, a problem existed: because wires have a small amount of resistance, over long transmission distances, a significant amount of power was lost as heat, resulting in a lower voltage at the receiving point. Therefore, electromagnetic switches and power sources were placed at relay points. Just as couriers would pass the message along in a relay, the power was amplified to reach the destination, which is why it came to be called a relay.

When discussing this topic, it’s also worth mentioning that using the earth can save on power lines for the return journey. To borrow Rudolf Steiner’s words, “The earth conducts electricity.”

After this explanation, we will actually build this mechanism.

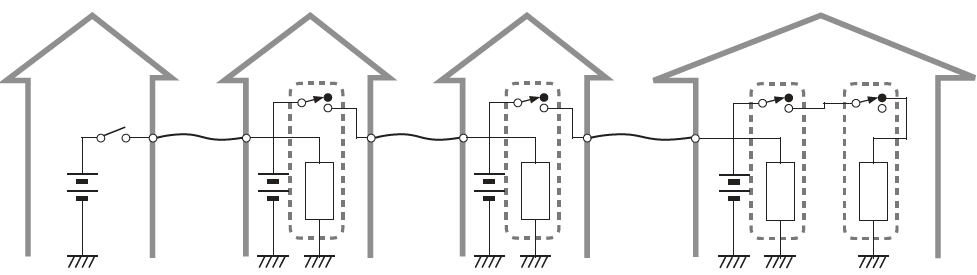

Create buffer circuits on workbenches at a suitable number of relay stations, prepare long enough wires to connect the stations, and add the negative feedback circuit created in the previous section to the final device. This will serve as the buzzer.

Connect a key switch, made by adding a contact point like a paper clip to the seesaw logic circuit, to the very first relay station.

The completed telegraph system reliably transmits switch operations from one end of the classroom to the other. The sight of the terminal buzzer sounding is spectacular, and the students are deeply impressed.

Later, when learning about internet technology, explain that the telegraph mechanism of transmitting information via electrical ON/OFF states is still used unchanged in the internet. It is crucial for students to grasp this concept.

Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

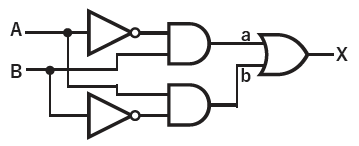

Now, we’ll finally get down to working on the adder.

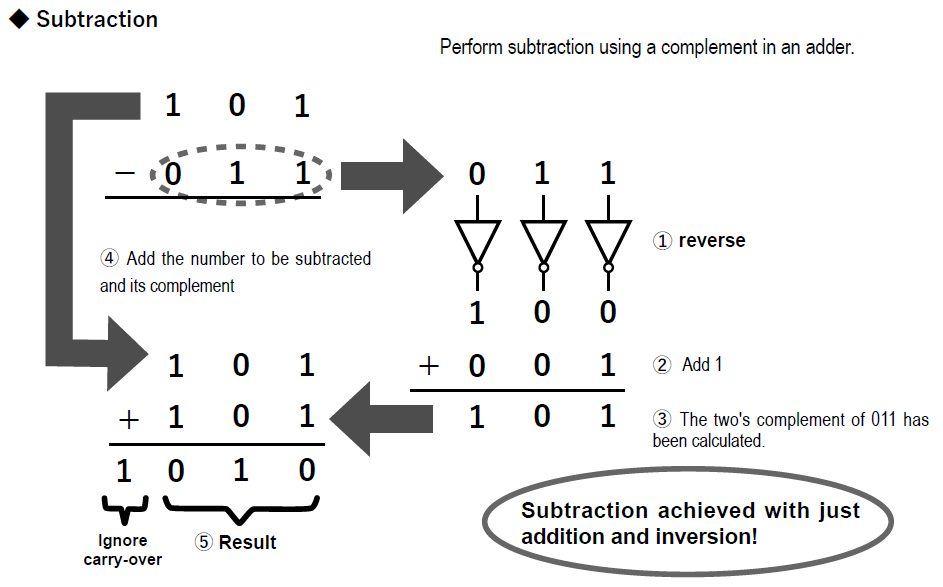

First, we clearly explain to students why we are building an addition device. Computer subtraction is achieved by adding the two’s complement, and both multiplication and division are simply shifting numbers and performing addition or subtraction. For these reasons, understanding how addition works is crucial.

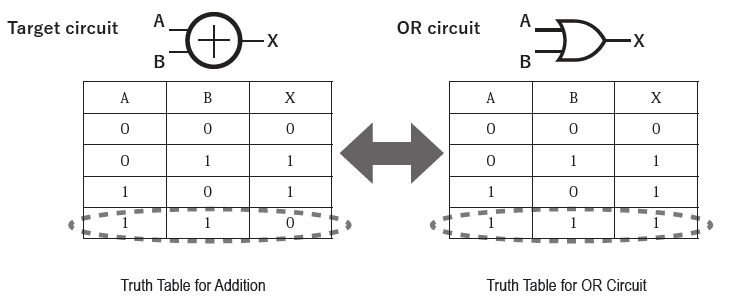

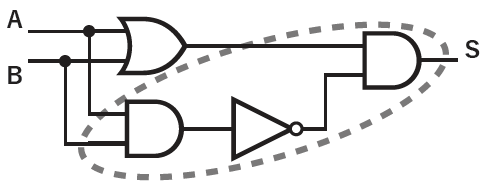

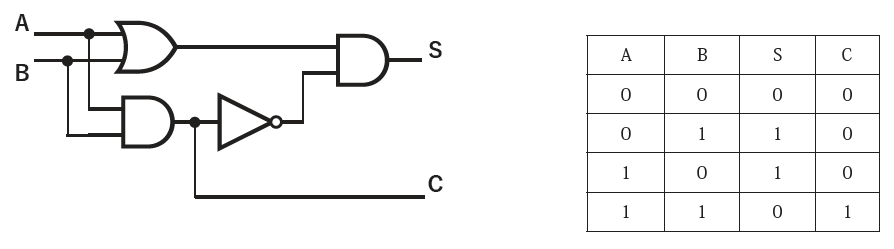

After clearly defining the goal in this manner, we demonstrate binary addition on the blackboard and consider how to implement the first-digit calculation using logic circuits. At this stage, we ignore carry-over and focus solely on the pattern of the first digit’s value. We then guide students to notice that this pattern closely resembles OR logic. Only the result of 1 + 1 differs from the pattern we seek.

Scientists and engineers around the world searched for the mechanism of a simple adder but couldn’t find it. With no other choice, they considered whether there was a way to force the OR circuit’s output to zero only when the input was 1+1.

The first thing to do is detect when the input is 1+1. It’s easy to see that this can be achieved with an AND circuit.

The next step was to find a mechanism that would force the OR circuit’s output to zero whenever the AND circuit’s output was 1.

This is a perfect opportunity to introduce the concept of a gate. I show my students the following well-known diagram:

(Surprisingly, the students become engrossed in these diagram.)

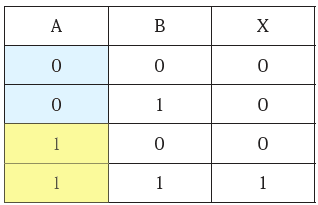

Humans possess the ability to discern different meanings by shifting their perspective on the same pattern. Let us observe the truth table of an AND circuit with the same eyes.

We then perceive a gate that opens and closes. When one input of the AND is 1, this gate opens, allowing the other input to pass through unaltered to the output. However, when the control input is 0, the gate closes, fixing the output at 0.

Through this interpretation, the AND circuit has also come to be characterized as a gate. Shall we apply this concept to our own adder?

This gate closes when the control signal is 0, so inverting the output of the AND gate used for the 1+1 detection earlier can serve as this signal.

This completes the implementation of the first digit of the addition.

Once you’ve gotten this far, the carry mechanism is straightforward. Since a carry occurs when 1 + 1, the output of the AND gate is precisely that. It was already implemented.

What this makes clear is that the standard computer’s addition circuit isn’t actually performing addition. What’s happening here is merely patching together a pattern of additions. Let’s confirm this with the students as well.

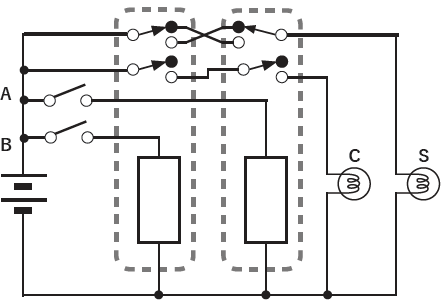

Relay Savings: Staircase Lighting System XOR Circuit

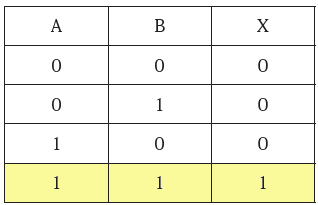

By now, we have understood the mechanism of a half-adder. Next, we will implement it using relays, and you can probably imagine that even this alone will require a fairly large-scale device. Simply put, we need four relays for the two AND circuits, two for the OR circuit, and one for the NOT circuit, totaling seven relays for this device.

Since each relay contains two switches, we can use two relays to create a set of OR and AND gates sharing inputs. Even so, this still requires five relays.

Our workbench only holds three relays, so we absolutely must find a way to save more.

So, I tell the students the following story: “Do you have stairs in your house? The staircase light can be turned on and off using switches, one on the lower floor and one on the upper floor. Let’s create a truth table showing the relationship between the states of these switches A and B and the light.”

Then, while showing the circuit diagram for the staircase lights, we create a truth table. Upon reorganizing the truth table, we will discover that a pattern of addition emerges there.

With this circuit, it’s possible to build an adder using just two relays. Since you can also build an AND circuit using the spare switches of the same relay, you can create a half-adder with just two relays. There’s no reason not to use this mechanism!

Regarding Group Work

To proceed with our work according to this policy, I’d like to consider group work.

Except for very small classes, workbench tasks are best done in pairs of two. Students can assist each other while working, and when creating truth tables, they can divide tasks—such as one person performing the operations and reading aloud while the other records the results.

Since we’ll ultimately build a full adder, the ideal setup is to form two pairs into a single island, working as a group of four.

We will form these groups from the very start when building the seesaw circuit and maintain them consistently throughout the work. For instance, each person will build their own seesaw NOT circuit, then pairs will combine them to form an OR circuit, and finally, the four members will collaborate to build the AND circuit.

In the telegraph experiment, one relay station is established per island, and the islands are connected by long lines.

This island group also functions well for handing out materials and then reflecting on or discussing them.

As students’ interest grows, some may leave the device powered on continuously to keep testing its operation, and others might even short-circuit the batteries.

As devices become more complex, it becomes problematic when they don’t function as expected and you can’t tell whether it’s due to wiring errors or depleted batteries.

For these reasons, I recommend having a battery checker available in the classroom. Whenever the wiring appears correct but the device behaves strangely, always check the batteries.

While commercially available battery checkers are fine, I use one I built myself. The advantage of a homemade version is that you can customize the pass/fail threshold to match the characteristics of the relay being used. Details like the circuit diagram will be covered in a separate article.

From full-adders to multi-digit adders

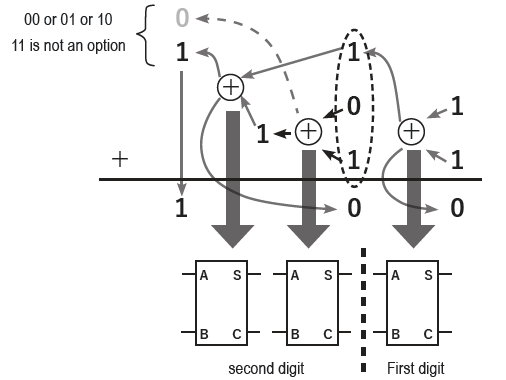

The mechanism of the full-adder is shown below.

The procedure from a half-adder to a multi-digit adder is shown below.

- Explanation of the Half Adder.

- Working in pairs, combine the previously examined staircase-style XOR circuit and AND circuit to form a half adder.

- Create a truth table for all input patterns and outputs to verify functionality.

- Explanation of the Full Adder.

- The two pairs present the half-adders they built, then combine the two units to form a full adder. Using spare relays from each workbench, they construct an OR circuit to combine the carries from the two half-adders. The collaborative effort of the four students culminates in a single achievement.

- Verify functionality.

- We will explain the wiring to connect multiple full adders to form a multi-digit calculator.

- We will implement a multi-digit calculator by arranging full adders on a large wagon-like table. The work of the entire class will manifest as a large device.

- We will verify it.

Starting with understanding logic, progressing through observing relays and practicing wiring, and conducting numerous experiments using relays, students who have become sufficiently familiar with the work can complete the above tasks in three days.

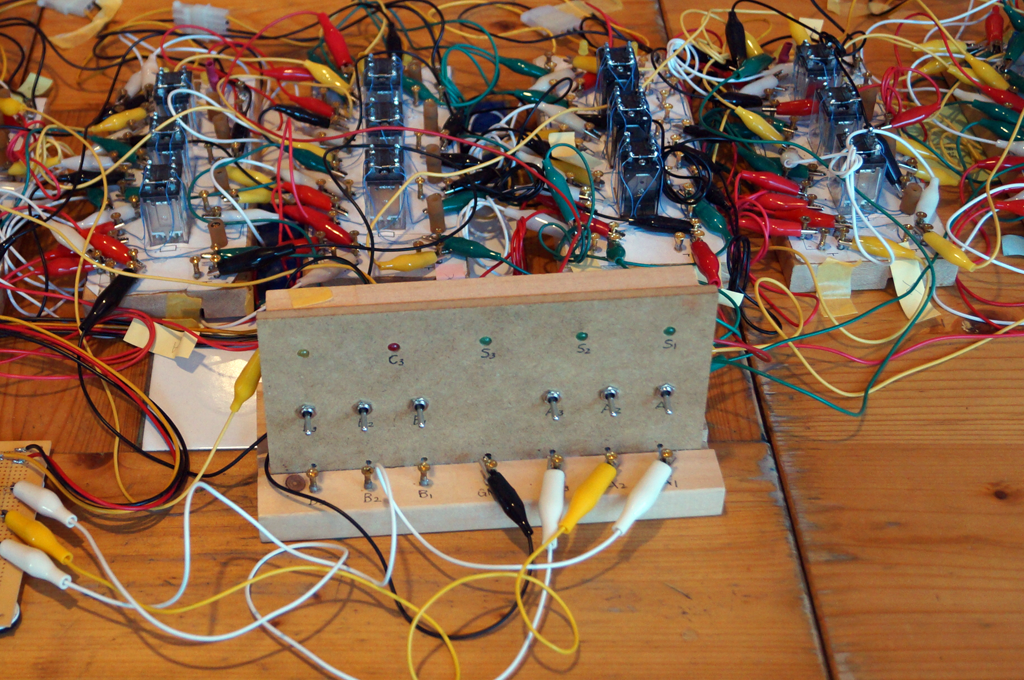

For the final verification of the multi-digit adder, three digits are appropriate. This yields 64 possible patterns, providing a manageable workload.

If possible, prepare an operation panel like the one shown below.

Assign two students: one to operate the circuit and the other to read out the results. The rest of the class will verify the results mentally while recording them on the pre-distributed log sheets. If an error is found, they should call it out immediately, and the wiring will be checked.

Starting with Switch B in the 0-0-0 state, set all 8 combinations of Switch A. Each time, read aloud the lamp value as 0 or 1.

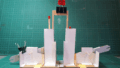

After working through about 3 blocks and confirming the results are correct, we will now connect the sequencer.

From Calculator to Computer

Verifying calculators by hand is a fun experience. But what if you had to do this all day long? Our predecessors developed computers to free humans from this task.

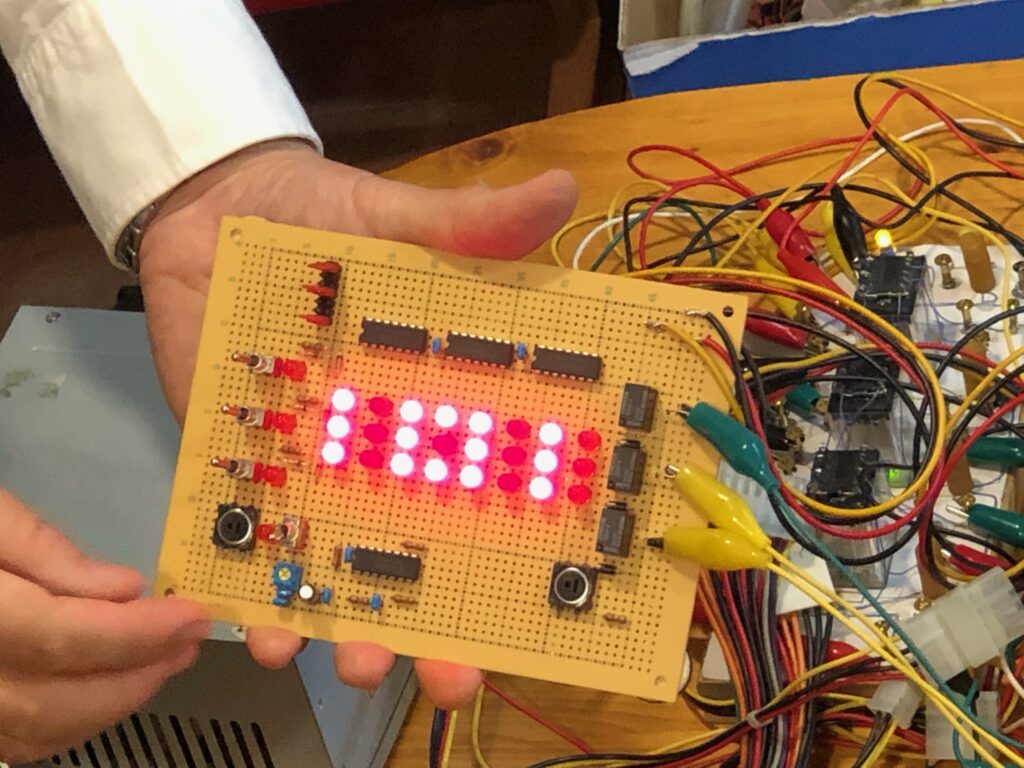

After discussing this, I show students a 3 x 8-bit sequencer and explain how it works.

- This arranges memory in an 8 x 3 grid, with lamps indicating the 0/1 state stored in each memory cell.

- The toggle switch on the far left allows you to specify the value to set in the memory.

- Pressing the push switch shifts all patterns one column to the right, writing the toggle switch setting into the leftmost column.

- The set information circulates from right to left.

- The information on the far right can control the input to an adder via a small relay.

It’s somewhat complex, but students grasp it quickly when explained through a live demonstration.

Once the students are satisfied, set binary patterns from 0 to 7 into this device and connect it to switch A of the adder. At this point, keep all the adder’s switches OFF.

Feed the binary data from the sequencer into the adder step by step. After confirming the adder operates correctly, use this method to verify all remaining patterns, completing the truth table for all 64 patterns.

Even this alone would make everyone think the work progressed quite smoothly. However, this still doesn’t qualify as an automatic machine.

Saying this, the teacher flips the switch on the sequencer’s clock circuit.

Exclamations of surprise should rise from the students. The monster machine they all built together began to move with a sound, as if it had been given life.

Yes, this is precisely the automatic machine Babbage and his followers sought to create.

I believe this sensory experience is the key to this learning. For them, the computer is no longer a black box.

This sequencer is designed to allow the clock speed to be controlled via a volume knob. By starting with the clock set very slow and saying, “Babbage’s Analytical Engine would probably run at about this speed,” then gradually increasing the speed while discussing, “The Z1 was around this,” and “The ENIAC felt like this. (Though it was actually much faster.)” students can gain a tangible sense of the relationship between clock speed and computer processing speed.

At that time, be sure to clearly confirm with the students that the sequence of lamps on the sequencer functions identically to the punch cards used in Babbage’s Analytical Engine.

Overview of the Computer System

To connect this to our future study of data models, we will delve deeper into how computers work. From here on, the entire lecture will be conducted on the blackboard.

The key point here is to stay focused on the image of punch cards as envisioned by Babbage and Zuse. There is no need to touch on von Neumann-type computers.

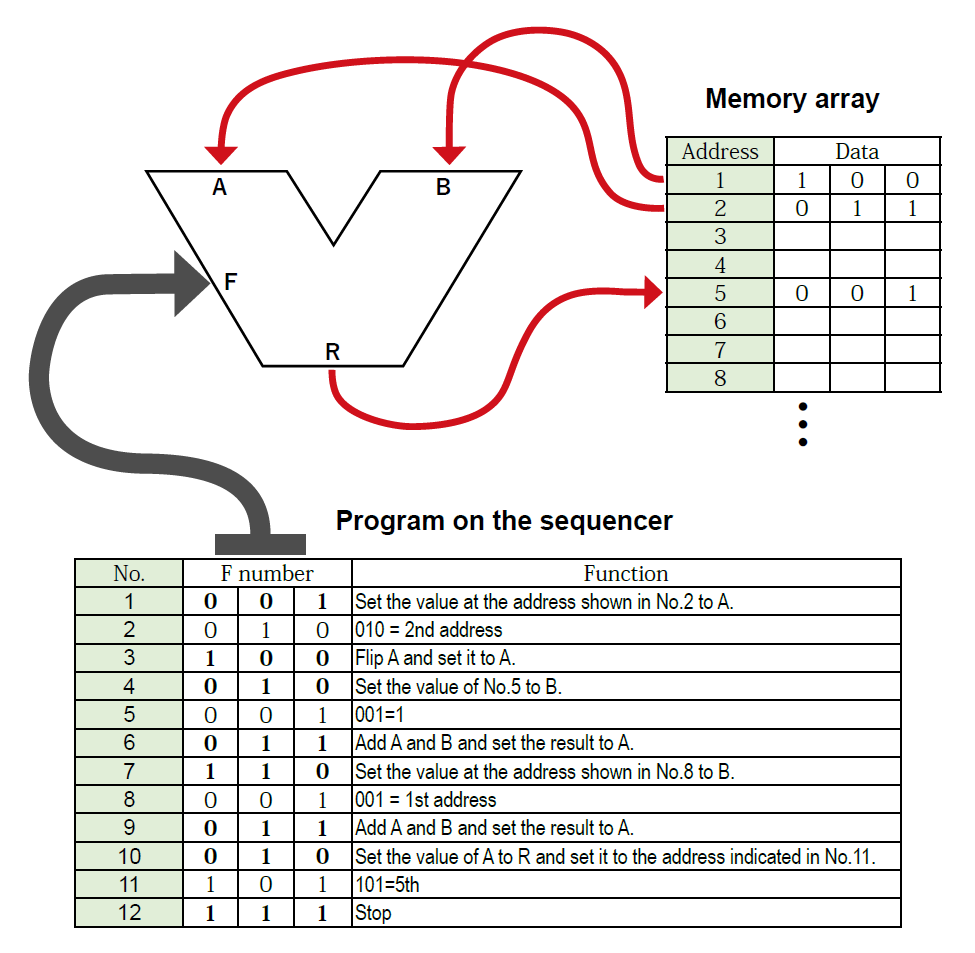

First, I’ll explain how a subtraction unit can be built from an addition unit using two’s complement. Furthermore, I’ll discuss how multiplication can be achieved through shift operations and addition, and division through shift operations and subtraction.

In this way, the four basic arithmetic operations become easily achievable. Based on this knowledge, we’ll now cover the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU). I’ll draw a large, striking V-shaped symbol for the ALU on the blackboard.

Furthermore, this device is designed like a buffet-style restaurant, with all computational and logical processing menus prepared in advance, allowing customers to select according to their requests(F).

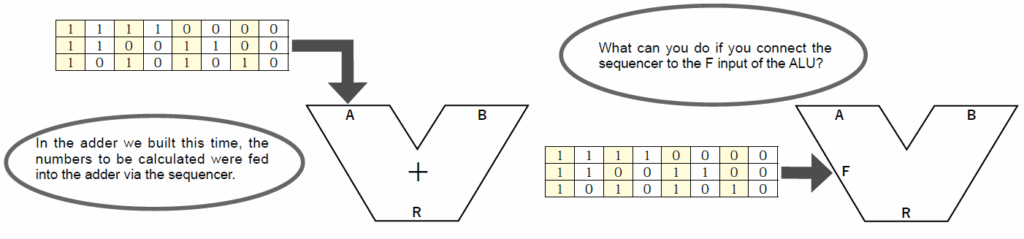

Here, the teacher confirms that in the previous calculation using the connected sequencer, automatic computation was performed by sequentially feeding the values set in memory into the adder’s numerical input. They then pose the following question to the students: So, what would happen if we set the operation processing steps in the sequencer and fed them into the ALU’s Function terminal?

Yes, this is how a computer executes a series of processes by sequentially feeding in procedures such as calculations and logical operations.

After sharing this image with the students, I explain that memory elements with assigned addresses are arranged inside the computer. The ALU repeatedly fetches data from memory, processes it, and returns the result to perform complex operations.

I use a program performing subtraction using two’s complement as an example. The students are surprised that even this simple operation requires a program with so many steps.

In reality, computers cannot produce the results humans intend without stacking up mountains of such tedious procedures. It’s only because computers perform these tasks extremely quickly that humans don’t consciously notice them. And once such tedious procedures are created, they can be reused, eliminating the need to recreate them each time.

In this way, computers have evolved through advancements in speed, increased memory capacity, and the technology for reusing programs.

Fundamentals of Information Processing

To wrap things up, I’ll briefly explain how computers handle various types of information internally.

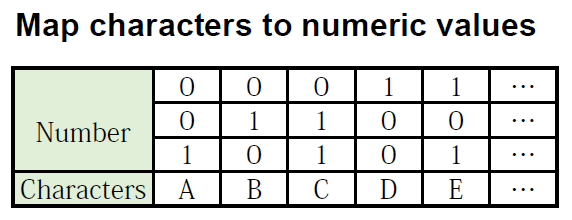

We already understand that they can handle numbers. So how do computers handle characters?

Ultimately, computers can only handle numbers. More precisely, they only handle patterns that humans have assigned numerical meaning to. It is humans who tie the concept of numbers to specific patterns.

Similarly, for characters, humans establish a one-to-one correspondence between a specific character and a numerical value. They then prepare a program that manipulates numerical information while keeping this relationship in mind, enabling the derivation of character processing results.

There is no need to explain this to students, but it is important that teachers understand this.

For students, simply show a table mapping numbers to letters. A simple one is best.

The crucial point is what example to choose for character processing. The best choice is search processing. Show an example of simple search processing and explain it.

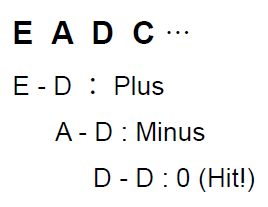

For example, suppose we’re searching for “D” within the string “EADC”. First, we extract the initial character, “E”. Of course, the corresponding numerical value for “E” is stored in memory, so we’re working with numbers. Here, the computer performs a subtraction operation: subtracting “D” from “E”.

If the result is not zero, it checks the next character. It checks “A,” then “D,” and only then does the result become zero. It has found the “D.”

This is a very simplified explanation, but this is the fundamental principle of search technology. Search is performed through subtraction. Even the pattern matching performed by AI is fundamentally subtraction. It’s simple. If students can grasp this impression, that is an educational achievement.

Character display is explained using the sequencer’s display. Simply setting and showing a pattern like 101 immediately convinces students. The computer isn’t displaying characters; it’s merely fetching the corresponding character shape patterns and arranging them in memory.

While we’re at it, turning the clock signal ON here also lets us explain how movies work. Two birds with one stone.

To explain how color displays work, we show them enlarged photos of RGB pixels. Having grown up with primary-color watercolors, they grasp it immediately.

It would also be helpful to briefly explain the mechanism for transmitting two-dimensional information.

Quantization of audio information can also be explained simply. Audio demonstrates that sound vibrations, as learned in acoustics, can be converted into voltage changes, which can then be digitized. Reversing this process—converting the numbers back into voltage and driving a speaker—reproduces the sound.

Finally, I/O.

Using the keyboard as an example, when you press the “A” key, the numerical value corresponding to the previously explained “A” appears. On the computer side, a free address is reserved within a column of memory, and the keyboard output is placed at that address. When the computer reads the contents of this address, it can obtain the value for “A”.

Output is the reverse process.

As described above, although somewhat rushed, we were able to provide students with a broad overview of computer systems within a single main lesson.

Internet

The final session of the 10-day program will cover the Internet. Details are covered in a separate section.

In closing

Summarizing all of the above content into ten lessons may be challenging at first. During the initial stages, we recommend allowing ample time for trial and error and proceeding at a relaxed pace. Conversely, once you become accustomed to the material, it is possible to conduct the course over five days with two sessions per day, such as during off-site classes when necessary.

After years of working on this, I firmly believe this lesson plan is an exceptionally effective practice because it allows students, regardless of gender, to gain a tremendous sense of fulfillment. After class, one student even said they were truly glad they could learn this before ever touching a computer. One student wrote in their notebook, “People all over the world should experience this class.” I feel the same way.

I am convinced that in our increasingly computerized society, this course—which allows students to touch upon the origins of computers and the essence of human beings—will only grow in value.

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Seesaw Logic Elements

- Clock and Memory

- The Origin of the Relay and the Telegraph Apparatus

- About the sequencer

- About the Battery Checker(Currently being produced)

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Integer type

- Floating-point type

- Character and String Types

- Pointer type

- Arrays

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)