Character type and String type

Created by Masashi Satoh | 1/19/2026

Title image source:Tom Scogland- Works by the contributor themselves, public domain, via links

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

Introduction

This article serves to reinforce the learning of “Learning Data Models.”

Character type

Character types are an extremely important mechanism that provides computers with an interface to humans through natural language. However, as already mentioned in the section on “Fundamentals of Information Processing,” the principle itself is very simple.

ASCII code set

Here, let’s look at character sets actually used as international standards. Below is the ASCII character set, a representative example of character sets covering the Latin alphabet.

| Lower hexadecimal digits | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | ||

| H i g h o r d e r | 0 | Control code | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ! | “ | # | $ | % | & | ‘ | ( | ) | * | + | , | – | . | / | ||

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | : | ; | > | = | < | ? | |

| 4 | @ | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | |

| 5 | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | [ | ] | ^ | _ | ||

| 6 | ` | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | |

| 7 | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | { | | | } | ~ | ||

The meaning of hexadecimal notation and why it is used are assumed to have been explained elsewhere.

This simple character set is represented using 7 bits of binary. To provide a clear overview, the lower 4 bits are plotted on the horizontal axis and the upper 3 bits on the vertical axis in a table. For example, the uppercase letter “M” is assigned the hexadecimal value 4D, which corresponds to the binary value 1001101.

A character type is a representation in memory of the numerical values corresponding to the letters and symbols we wish to express, following this code set. Let’s firmly grasp this concept first.

(hexadecimal) 41 → A (The concept of characters as expressed)

What I want to confirm with the students is that the character placement in this code set starting with hexadecimal 20 is not inevitable; it would be perfectly fine if it started with 0. Similarly, the starting positions of uppercase and lowercase letters, or the placement of symbols, are not fixed by necessity.

It’s good to know that the arrangement of a character code set has settled into this configuration due to various historical circumstances, the interests of the companies using it, and cultural factors like the aesthetic appeal of the arrangement. This reveals the human presence behind it. If you look into it, you’ll likely find numerous human-centered anecdotes.

The Difference Between Typewriters and Computers

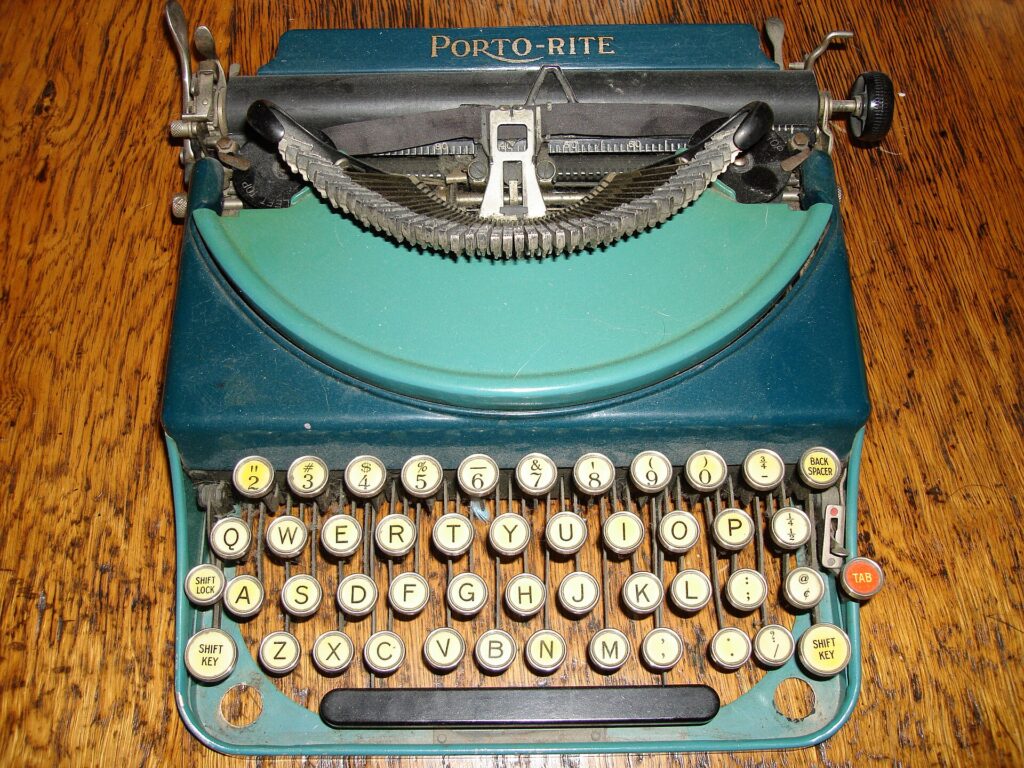

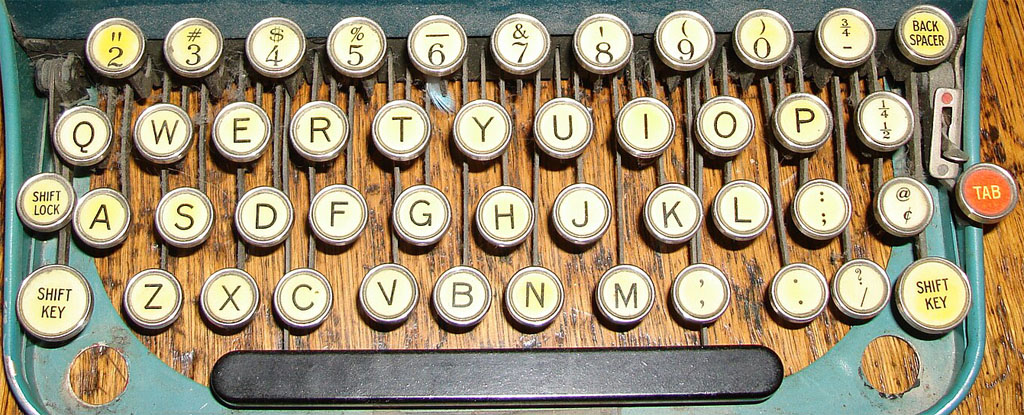

Now, show the students a photo of an old typewriter.

Since most students have likely never seen a mechanical typewriter, briefly explain how it works. They’ll quickly recognize that the keyboard on modern computer terminals directly follows the typewriter style. You could also delve into the meaning of control characters like carriage return and line feed in relation to this.

Then, draw the students’ attention to the missing “1” key where it should be in the top-left corner. Is this a broken typewriter with a missing key? No. This is the standard key layout for typewriters of that era.

“Why did they arrange the keys like this? What should I do when I want to type the number 1?” Asking this question will spark a fun exchange. Maybe a student will suggest, “Why not use ‘I’ or ‘l’ instead?”

The fact is, that’s exactly what happened. To save on mechanical parts, back then they substituted the number ‘1’ with the lowercase letter “L”. With typewriters, only the “how it looks” aspect of the impression mattered, making such abbreviations possible. However, omitting the number “1” on a computer keyboard is unthinkable. Computers require processing the number 1 and the lowercase letter L not by their shapes, but as information tied to their respective character concepts.

Typewriters can serve as excellent teaching tools for recognizing the importance of this difference.

Now, let’s focus on the arrangement of symbols on the top row of a typewriter. Students should notice that the sequence of symbols from hexadecimal 20 to 2F in the ASCII code set closely resembles the top row of a typewriter.

| ! | “ | # | $ | % | & | ‘ | ( | ) | * | + | , | – | . | / |

In this way, computer technology has consistently incorporated preceding technologies and cultures while establishing the necessary definitions and standards to make the technology viable.

Representation of characters in memory

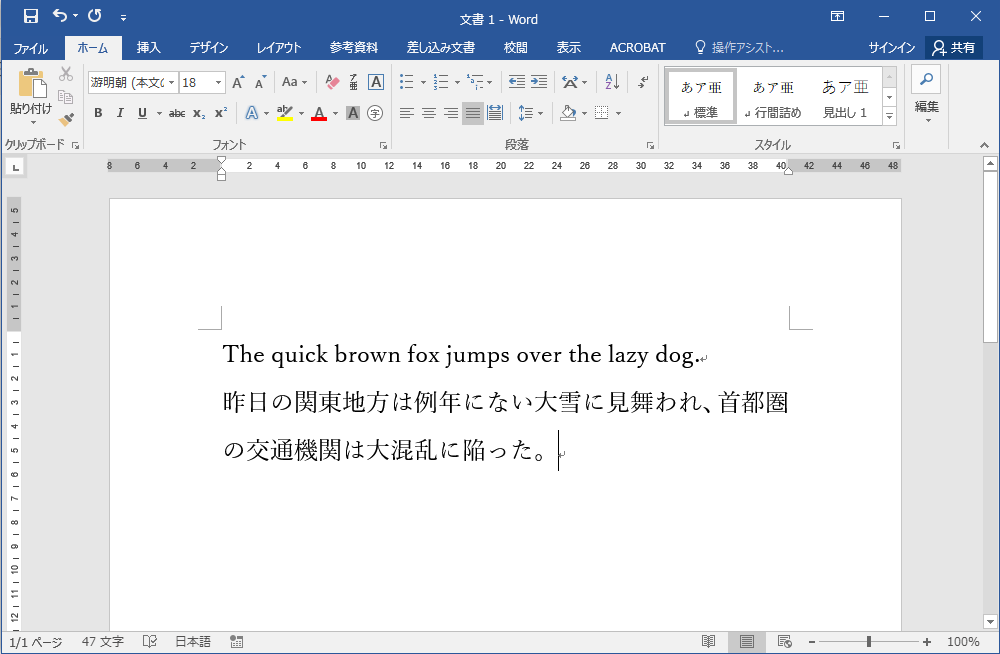

By arranging the character code set defined in this way in memory, the computer can process text. Below is the representation of “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” in memory using the ASCII code set. To make word boundaries easier to see, the space code hexadecimal 20 is shown in yellow.

54686520717569636B2062726F776E20666F78206A756D7073206F76657220746865206C617A7920646F672E

When this sequence of hexadecimal values is compared against the ASCII code set, it can be seen that it corresponds to the following:

The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

This made it possible to represent natural language on computers. What appears as a sequence of numbers in memory is linked to human-defined character code tables and corresponding character concepts, allowing humans to understand it as text. Let’s confirm that the computer itself does not understand this information as text.

The Importance of Rule-Making and Standardization

Another point to note is that a character code set has little practical value if it is defined only for this specific context. A character code only gains value when agreements are made between companies or nations to ensure its interoperability, and when it becomes a standardized specification.

For example, here is a table showing the EBCDIC code used on mainframes. Students will likely be surprised to see how dissimilar its code arrangement is to ASCII. Naturally, the two are incompatible. When exchanging documents between systems, conversion programs are required. However, the reason EBCDIC has this particular sequence lies in its development history, based on Binary-Coded Decimal (BCD), a numerical representation used to prevent rounding errors in decimal calculations.

Thus, exchanging information necessitates consensus among those involved in the exchange.

Today, the Unicode character encoding set has become the foundational technology supporting the internet that connects the world, encompassing character information for languages worldwide. To establish its standards, the non-profit Unicode Consortium was founded, bringing together language experts and engineers for extensive discussions.

While universalist ideals are championed there, attention must also be paid to the complex negotiations resembling territorial disputes over who (which language’s characters) occupies prime real estate on the map of numerical information. Discussions continue on how to represent characters with complex structures and on the dizzying question of how much variation, such as alternate forms of characters, should be included. This is a theme that strongly resonates with students in their formative years.

Characters as numbers

Now, let’s return to the topic of character types.

Earlier, I mentioned that the specific numerical values assigned to each character aren’t particularly significant. What matters is that specific character concepts are uniquely associated with specific numerical values. However, when humans handle alphabets or the 50 sounds of hiragana, they organize and understand them in sequence, like abcdefg… or あいうえおかきくけこ…. To represent this cultural practice on a computer, we must confirm that these character concepts need to be mapped to ordinal values.

Furthermore, representing character concepts numerically enables the conversion between uppercase and lowercase letters through calculation. In the ASCII code set, the difference between uppercase A and lowercase a is 20 in hexadecimal, or 32 in decimal. Therefore, simply adding or subtracting 32 allows for case conversion.

For humans, this means converting between uppercase and lowercase, but note that the computer simply performs the calculation as instructed.

And as we saw earlier, performing subtraction allows us to compare characters. This is the most fundamental technique for searching.

So, how can we convert a binary number into its decimal numerical representation? Let’s have the students think about it. This also seems calculable.

Yes, dividing the value to be converted by 10 gives a remainder that corresponds to a single decimal digit. Adding the ASCII code value for ”0” (hexadecimal 30, decimal 48) yields the corresponding ASCII character. Then, subtract this remainder from the original value and repeat the process, shifting the digits upward.

Students will likely be surprised that representing numbers as characters requires such a cumbersome procedure. Behind the glittering user interface, the machine—the computer—diligently carries out this dirty work, following instructions without question. It’s crucial for them to at least vaguely imagine this process.

String type

Earlier, we confirmed that we can represent text by arranging character types in memory.

The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

However, when actually handling this sequence of strings, there is something we must consider. That is, the length of the string varies depending on the text. With an integer type, the size is always constant, so we simply need to read the bit sequence of the integer size from that address. With strings, this is not guaranteed.

Both character information and numerical data are merely patterns in memory to the computer. Therefore, humans must demarcate the boundaries, defining “this part is a string.” What mechanisms can be devised to ensure that even if the string length varies, the range within that length can be appropriately processed as a coherent sequence of character information?

This is also a good topic to have students think about.

First, assume we know where the beginning of the string is.

One method is to place a terminator character. For example, since control codes in the ASCII code set are not used for representation, we could place one of these at the end of the string as a marker indicating its terminus. Here, let’s place 0 (the NUL control code).

The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.NUL

Starting from the beginning of this string and scanning sequentially, whenever a ‘0’ is found, the character immediately preceding it marks the end of the string.

While this approach is very straightforward, it has a slight drawback. You must check the entire string from the beginning until the terminator character appears to determine its length.

Students will likely suggest: “Why not store the length information as a set?”

Exactly. Consider the following data structure: one integer type to hold the character count, and a sequence of character types whose length is indicated by that count.

Character count:44 The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

This makes handling much simpler. Most string types take this form.

Advanced String Manipulation

Next, let’s consider operations on strings, which are sequences of characters.

The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

As mentioned above, we have already learned that strings can be represented by arranging characters (actually, the IDs corresponding to characters, i.e., numerical values) in memory. So, how can we replace the above “brown” with “white”?

The_quick_brown_fox

↑

white

In this case, we can see that we simply need to replace “brown” with “white.” So, how can we replace “brown” with “gleaming”?

The_quick_brown_fox

↑

gleaming

At this rate, the three letters “ing” won’t fit!

After “ fox…”, simply shift the characters to the right and write “ing” in the space that opens up.

The_quick_brown>>>_fox

↑

gleaming

So, what about replacing “brown” with “red”?

The_quick_brown_fox

↑

red

This time, conversely, we need to shift everything after “wn fox…” back by two characters. First, replace “bro” with “red”, then perform the following operation.

The_quick_brown_fox

The_quick_red<<_fox

The_quick_red_fox

This is the fundamental concept behind string manipulation.

However, creating word processor software using this method is impractical. What if the text being handled is extremely long, perhaps the length of an entire book?

If many more sentences followed the text above, the task of endlessly shifting that massive string of characters two characters forward would be required. Since such a large amount of work would occur every single time for even a small change, it is clearly inefficient.

This task of moving characters means, for the computer, repeatedly taking out the contents of memory and writing them back.

Let’s confirm with the students that even very high-performance computers struggle with this kind of task. This is because, compared to the processing speed of modern high-performance CPUs, the speed of reading and writing to memory is extremely slow. Since it involves repeatedly reading from slow memory and writing to slow memory, even a high-performance computer can’t help it.

We refer to such operations as “costly operations,” which could also be described as highly inefficient operations.

So, is it possible to perform the above operations at a “low cost”?

Pointers are a mechanism designed precisely for this purpose: to efficiently handle large chunks of information.

Pointers are very similar to IDs. While an ID is a symbol representing a specific concept, a pointer holds the location—the address—where specific information is stored in memory. The information you seek is located at the address indicated by the value held by the pointer.

Since pointers only hold address information, the type and size of the information stored there must be managed as separate information. Following this concept, let’s represent the example from the previous paragraph in memory.

Address”The quick…” Pointer-type information

Count”The quick…”: 44 Integer-type information

↓Indicate the location and length of the following string.

The_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

A string is represented as a set consisting of the string entity itself, a pointer indicating the starting position (address) of that string, and numerical information about the string’s length. In this example, the pointer-type data points to an address containing string information starting with “The quick”, and indicates that its length is 44 characters.

This set of three pieces of information is considered the string type. It follows the same concept as the floating-point type being composed of an exponent and a mantissa. (As previously learned, there are other ways to represent string types, but they are all called string types in the sense that they are types for handling strings.)

Handling text with such an information set dramatically improves the efficiency of string operations. Let’s look at an actual operation.

Using this information, let’s insert “gleaming ” before “brown.” First, prepare the string “gleaming ” separately from the sentence.

Address”greaming” Pointer-type information

Count”greaming”: 9 Integer-type information

greaming_

Next, split the string “The quick…” at the position of the ‘b’ in “brown”. The method is simple: create a new pointer indicating the relevant position, recalculate the number of characters in the string segmented at this split point, and assign it.

Address”The quick…”Count”The quick…”: 44

The_quick_brown_fox…

↑ Split here

The original string has been split, creating a new string starting with “brown…”.

Address”brown…”Count”The quick…”: 34

brown_fox_jumps_over…

Then you just need to adjust the number of characters in the original string “The quick” to match the number of characters after splitting. Here, it’s 10 characters.

Address”The quick…”Count”The quick…”: 10

The_quick_

With this simple operation, we’ve split the long sentence starting with “The quick…” into two strings at the “brown…” part!!

Then, you just need to figure out how to insert the string “gleaming” between these two strings.

What’s important to note here is that the pointer and character count information do not need to be stored in the same location as the actual string. Since the pointer knows where the string is located, there is no reason they must be kept together.

Using this property, we can collect and arrange the pointer and character count information for each string as follows.

Address”The quick “Count”The quick “: 10

Address”gleaming “Count”gleaming “: 9

Address”brown fox…”Count”The quick “: 34

How does this sound? Connecting these three sentences is the goal we aimed for—inserting “gleaming” between “The quick” and “brown fox.”

Even when we say “splitting a sentence and inserting words in between,” it should be understood that there’s no need to move the character information itself. It’s sufficient if we can treat the three strings above as a single continuous sentence. We simply follow the pointers in order, read the strings they point to, and concatenate them one after another.

This mechanism allows us to handle large strings with little difference in effort, whether they are continuous or split.

The total character count for the entire text also doesn’t require counting every single character. It can be determined by summing the character count information associated with each pointer.

If you need to reassemble a string that was split for some reason, you allocate memory for the total character count and then copy the split strings back in order.

Allocate memory for the entire character count

Memory area addressCharacters secured: 53(10 + 9 + 34)

The_quick____________________________________________

Copy “The quick ”

Address“The quick ”Character count:10

↓

The_quick____________________________________________

Copy “gleaming ”

Address“The quick ”Character count:9

__________ ↓

The_quick_gleaming___________________________________

Copy “brown fox…”

Address“brown fox…”Character count:34

____________________↓

The_quick_gleaming_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

Desired outcome

Address“brown fox…”Character count:53

The_quick_gleaming_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog.

In this way, combining pointer types, integer types, and character types allows us to build an extremely flexible string manipulation mechanism. Whenever handling information whose length can change, like strings, pointer types are always essential.

Since even the largest data can be cut, joined, or rearranged with just a single pointer, this is an indispensable technique for handling vast amounts of information. Blockchain technology, for example, can be said to have its roots in the concept of a list structure using pointer types.

I plan to delve a bit deeper into pointer types in a separate section.

Finally, if time permits and the students show strong interest, you might mention the mechanism of memory allocation. In the example above, you could touch on how the memory space allocated for concatenating text is prepared, and what processing is required to free the memory used by the concatenated text fragments.

So far, we’ve looked at what character types and string types are.

As we’ve seen, within computers, phenomena and concepts from the real world are represented using data structures that combine multiple pieces of information. People have imbued meaning into and organized the meaningless grid of memory, creating various mechanisms. Word processors are one such achievement.

Actually running a word processor here will strongly impress upon students what they have learned. Behind the word processor, the text entered by the user via the keyboard is manipulated using mechanisms like those we have seen.

- Shaping the spine of the ICT curriculum in Waldorf education

- The History of Computers(Currently being produced)

- Details on Constructing an Adder Circuit Using Relays

- Seesaw Logic Elements

- Clock and Memory

- The Origin of the Relay and the Telegraph Apparatus

- About the sequencer

- About the Battery Checker(Currently being produced)

- Internet

- Learning Data Models

- Integer type

- Floating-point type

- Character and String Types

- Pointer type

- Arrays

- Learning Programming and Application Usage Experience(Currently being produced)

- Human Dignity and Freedom in an ICT-Driven Society(Currently being produced)

コメント